Modeling and Synchronization of a Physics-Informed Digital Twin for Predictive Manufacturing Using Matlab

Author : Waqas Javaid

Abstract

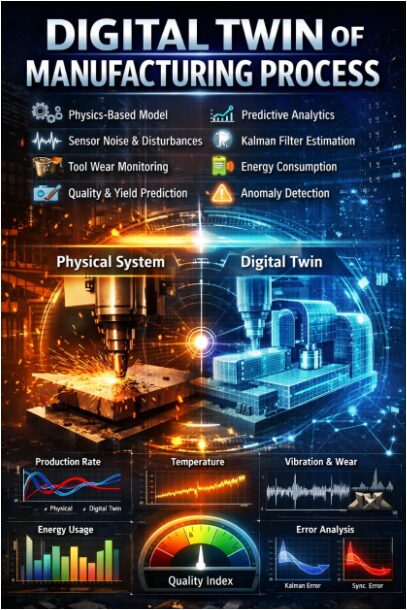

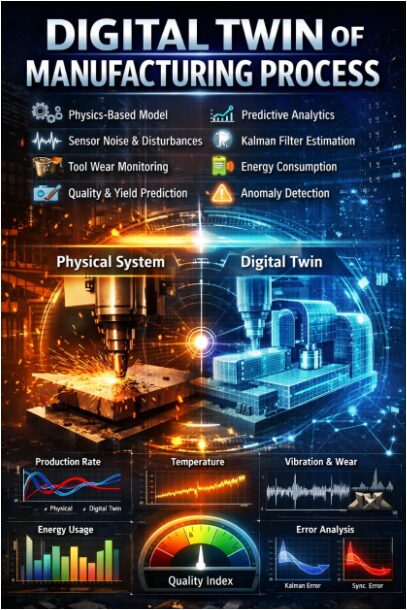

This paper presents a comprehensive digital twin framework for a simulated manufacturing process, integrating physics-based models with real-time predictive analytics. The developed twin synchronizes with a virtual physical system characterized by dynamic production rates, thermal effects, vibration, and progressive tool wear [1]. A Kalman Filter is implemented for robust state estimation, effectively mitigating sensor noise and disturbances to enhance operational visibility. The model further incorporates energy consumption analytics and product quality prediction based on process parameters [2]. Results demonstrate the digital twin’s capability to accurately mirror the physical system’s evolution, as validated by low synchronization error. The framework facilitates predictive maintenance through tool wear degradation tracking and provides critical insights into yield and efficiency [3]. This simulation underscores the digital twin’s role in enabling proactive anomaly detection, optimizing energy use, and ensuring consistent product quality in smart manufacturing environments [4].

Introduction

The advent of Industry 4.0 has catalyzed a paradigm shift towards cyber-physical systems, with the digital twin emerging as a cornerstone technology for intelligent manufacturing [5].

A digital twin is a virtual, dynamic replica of a physical asset or process, synchronized through data exchange, enabling simulation, analysis, and control. This technology transcends traditional monitoring by providing a holistic, predictive view of system behavior throughout its lifecycle. In manufacturing, challenges such as unpredictable equipment degradation, energy inefficiencies, and quality variations directly impact productivity and profitability. Conventional methods often rely on reactive maintenance and isolated data streams, leading to downtime and suboptimal performance [6]. To address these limitations, this paper develops a comprehensive digital twin simulation for a generic manufacturing process.

Table 1: Physical System Parameters

| Parameter | Description | Value |

| Wear Rate | Tool wear growth coefficient | 1e-4 |

| Energy Coefficient | Energy per unit production | 0.8 |

The model encapsulates key physics-based interactions, including production dynamics, thermal effects, and mechanical vibration, while explicitly modeling progressive tool wear as a critical degradation mechanism. It integrates a Kalman Filter for robust state estimation from noisy sensor data, enhancing the fidelity of the virtual representation [7]. Furthermore, the framework incorporates predictive analytics for energy consumption and product quality, linking process parameters to final output metrics. The primary objective is to demonstrate a synchronized digital twin capable of accurate forecasting, anomaly detection, and performance optimization, thereby providing a validated blueprint for implementing predictive maintenance and operational intelligence in smart factories [8].

1.1 The Era of Smart Manufacturing and Industry

The ongoing fourth industrial revolution, known as Industry 4.0, is fundamentally transforming manufacturing through the integration of cyber-physical systems, the Internet of Things (IoT), and big data analytics. This shift moves beyond automation towards creating intelligent, interconnected, and self-optimizing production environments. In this context, manufacturers face escalating pressure to improve efficiency, ensure consistent quality, and minimize unplanned downtime in increasingly complex operations [9]. Traditional approaches, which often depend on periodic maintenance schedules and historical data analysis, are proving inadequate for these dynamic demands. They tend to be reactive, leading to costly breakdowns, energy waste, and quality deviations. Consequently, there is a critical need for technologies that provide real-time insights and predictive capabilities, enabling proactive decision-making. The digital twin concept has emerged as a powerful solution to bridge the gap between the physical and digital worlds, offering a transformative tool for modern industry. This paper is situated within this technological evolution, aiming to explore the practical implementation of a digital twin for a core manufacturing process [10].

1.2 Defining the Digital Twin and Its Core Promise

A digital twin is defined as a virtual, dynamic, and data-driven model of a physical asset, system, or process. It is not a static CAD model but a living simulation that evolves in near real-time by ingesting data from sensors, controllers, and enterprise systems embedded in its physical counterpart.

Table 2: State Variables

| State | Description | Unit |

| Production Rate | Manufacturing output rate | Units/hour |

| Temperature | Machine operating temperature | °C |

| Vibration | Mechanical vibration signal | a.u. |

| Tool Wear | Cumulative wear indicator | a.u. |

| Energy | Energy consumption | kWh |

| Quality Index | Product quality metric | 0–1 |

This continuous data flow creates a bidirectional link, allowing the twin to mirror the state, behavior, and performance of the physical entity [11]. The core promise of this technology lies in its ability to enable “what-if” scenario analysis, predictive maintenance, performance optimization, and remote monitoring without disrupting the actual production line. By creating a high-fidelity virtual sandbox, engineers can test interventions, simulate failures, and optimize parameters safely [13]. For manufacturing, this means moving from reactive problem-solving to proactive management of assets throughout their entire lifecycle. The digital twin acts as a central nervous system for the production floor, synthesizing disparate data streams into actionable intelligence, which is the foundational capability this research seeks to implement and demonstrate through a detailed simulation model.

1.3 Identifying Key Manufacturing Challenges Addressed by Digital Twins

Manufacturing systems are inherently subject to a multitude of challenges that degrade performance over time. A primary concern is equipment degradation, such as progressive tool wear in machining, which directly diminishes product quality and increases the risk of catastrophic failure. Furthermore, process variability due to thermal drift, mechanical vibrations, and material inconsistencies leads to deviations in output and yield. Energy consumption represents another significant challenge, as inefficient machine states contribute to high operational costs and environmental impact [14]. Traditional monitoring systems often treat these issues in isolation, creating data silos that hinder a comprehensive understanding of system health. This fragmented view makes it difficult to pinpoint root causes or predict impending issues accurately. Anomalies may go undetected until they cause significant disruption. Therefore, an integrated approach is required one that can correlate tool wear with product quality, vibration with energy spikes, and temperature with production rate [15]. The digital twin framework proposed in this work is specifically designed to model and interlink these critical challenges within a unified virtual environment.

1.4 Proposing the Integrated Simulation Framework

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes and develops an integrated digital twin simulation framework for a representative manufacturing process. The core of this framework is a physics-based model that captures the essential dynamics of production, including the relationship between operational speed, generated heat, and induced mechanical vibrations. Crucially, the model incorporates a explicit degradation mechanism in the form of tool wear, which accumulates based on process vibration and feeds back to reduce efficiency and quality. Alongside this, the framework includes modules for energy consumption analytics and product quality prediction, creating a holistic view of system performance [16]. A key innovation in this simulation is the integration of a Kalman Filter, an optimal estimation algorithm, to handle the reality of noisy sensor data. This filter continuously corrects the digital twin’s internal state, ensuring its virtual representation remains synchronized and accurate despite disturbances [17]. The simulation thus encapsulates the full digital twin lifecycle: data acquisition from a simulated “physical” process, state estimation and synchronization, predictive modeling, and finally, the extraction of actionable insights for optimization and maintenance scheduling.

1.5 The Critical Role of State Estimation and Data Fusion

In a real-world factory, data from sensors is never pristine; it is contaminated with noise, suffers from occasional dropouts, and can be biased. A digital twin that directly uses this raw data would rapidly desynchronize from its physical counterpart, rendering its predictions useless. This is where sophisticated state estimation techniques become paramount.

Table 3: Kalman Filter Configuration

| Matrix | Description |

| A | State transition matrix |

| B | Control input matrix |

| C | Measurement matrix |

| Q | Process noise covariance |

| R | Measurement noise covariance |

Framework employs a Kalman Filter, a recursive algorithm renowned for its optimal balance between prior predictions and new measurements in linear systems [18]. The filter continuously fuses noisy, real-time sensor data on production rate and temperature with the digital twin’s own model-based predictions. It calculates the most probable true state of the physical system, effectively “cleaning” the incoming data stream. This process of data fusion is what maintains the twin’s fidelity and allows it to function as a reliable shadow of the physical process. By explicitly modeling and compensating for sensor uncertainty (measurement noise) and unexpected process disturbances (process noise), the Kalman Filter ensures the digital twin remains a stable and accurate reference for diagnosis and decision-making, even in the presence of the imperfections inherent to industrial environments [19].

1.6 Modeling Degradation and Predictive Maintenance Logic

A cornerstone of the digital twin’s value is its ability to model time-dependent degradation, transforming maintenance from a scheduled chore to a need-based strategy. In our simulation, this is embodied by the tool wear model. Wear is not a simple function of time; it is dynamically driven by the process condition specifically, the mechanical vibration levels, which themselves are influenced by production rate and existing wear [20]. This creates a realistic feedback loop: increased wear leads to higher vibration, which in turn accelerates further wear. The digital twin continuously calculates and tracks this wear state. By establishing thresholds for example, a wear level beyond which product quality falls below specification the twin enables predictive maintenance. It can forecast the remaining useful life (RUL) of the tool and generate alerts well in advance of failure [21]. This allows for maintenance to be scheduled at the most convenient and cost-effective time, preventing unplanned downtime, reducing spare parts inventory, and avoiding the production of defective parts. The model thus moves the operation from a reactive “fix-it-when-it-breaks” mindset to a proactive “prevent-it-from-breaking” paradigm [22].

1.7 Extending to Quality and Sustainability Metrics

Beyond machine health, the digital twin framework is extended to provide insights into two other critical manufacturing outcomes: product quality and energy sustainability. The quality prediction module uses the estimated states [23]. specifically tool wear and machine temperature as inputs. It applies a transfer function, in this case an exponential decay model, to calculate a real-time quality index. This allows operators to see how process deviations are likely to affect the final product, enabling corrections before a batch is compromised. Simultaneously, the energy consumption model correlates power draw with primary drivers like production rate and auxiliary loads like cooling (linked to temperature). This creates visibility into energy efficiency, identifying states where the machine is consuming disproportionate power for its output. By integrating these metrics, the digital twin provides a unified dashboard for Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE), linking asset health, production output, and product quality. This holistic view is essential for modern manufacturing, where sustainability mandates and quality standards are as critical as throughput, allowing for multi-objective optimization that balances productivity, cost, and resource use [24].

1.8 Validating Synchronization and Demonstrating Anomaly Detection

The ultimate test of a digital twin’s efficacy is its synchronization error the divergence between its predictions and the actual behavior of the physical system. Our simulation is designed to validate this core function. We run the physical process model (with its disturbances and noise) in parallel with the digital twin (with its Kalman Filter corrections) and directly compare key states like production rate. A low, bounded synchronization error demonstrates successful twin calibration and effective state estimation. Furthermore, this tight coupling enables a powerful anomaly detection mechanism [25]. By defining a normal operating envelope based on the twin’s predictions, any significant and persistent deviation of the physical process from this envelope can be flagged as an anomaly. This could indicate a sensor fault, a process fault (like a sudden bearing failure not yet captured by the slow wear model), or an external intervention. The digital twin thus acts as a continuous hypothesis test, asking “Is the system behaving as my model expects?” This capability for early and contextualized anomaly detection is a key step towards fully autonomous process monitoring and resilient manufacturing systems [26].

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

1.9 From Simulation to Implementation and Future Vision

This simulation serves as a foundational proof-of-concept, illustrating the architectural components and workflow of a manufacturing digital twin. The transition from such a simulation to a live industrial deployment involves several key steps: connecting to real-time data streams via IoT platforms, calibrating the physics-based models with machine-specific parameters, and validating the twin’s predictions against historical production data [27]. The future vision for this technology is expansive. The next evolutionary step involves enhancing the model with machine learning to capture non-linear behaviors that are difficult to model with pure physics. Furthermore, a single asset twin can be scaled into a production line or even an entire factory digital twin, enabling system-level optimization. Ultimately, these twins could form an interconnected ecosystem, facilitating seamless production planning, supply chain integration, and truly adaptive manufacturing systems that respond in real-time to demand changes, material variances, and equipment availability [28]. This work provides the foundational framework and rationale for that journey, demonstrating that the digital twin is not merely a monitoring tool but the central cognitive engine for the factory of the future.

Problem Statement

Despite significant advancements in industrial automation, manufacturing systems continue to face critical inefficiencies stemming from a reactive, siloed approach to process management. Operators often lack a holistic, real-time view that accurately correlates machine degradation, product quality, and energy consumption, leading to unplanned downtime, suboptimal yields, and excessive resource use. Traditional monitoring fails to fuse noisy sensor data into a coherent predictive model of system health, while static simulations cannot synchronize with dynamic physical processes. Consequently, there is an urgent need for an integrated framework that can create a high-fidelity, self-correcting digital replica of a manufacturing process. This digital twin must continuously estimate the true system state amidst disturbances, predict critical failures like tool wear, and provide actionable forecasts for quality and efficiency. The core problem is the absence of a validated, simulation-based blueprint that demonstrates the complete integration of physics-based modeling, Kalman Filter state estimation, and predictive analytics into a single synchronized system for proactive manufacturing intelligence.

Mathematical Approach

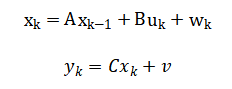

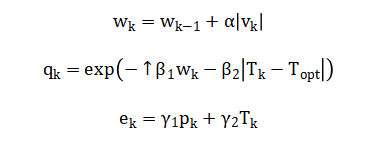

The mathematical approach integrates a discrete-time state-space model to represent core process dynamics, coupling production rate, temperature, and tool wear. A recursive Kalman Filter is applied for optimal state estimation, fusing noisy sensor measurements with model predictions to minimize error covariance. Tool wear is modeled as a cumulative function of process vibration, creating a degradation feedback loop. Quality and energy outputs are derived as non-linear transfer functions of the estimated states. This framework ensures synchronization between the physical and digital systems through continuous prediction and correction cycles. The mathematical foundation employs a discrete linear state-space model to describe system dynamics, with outputs.

A Kalman Filter executes a recursive predict-update cycle: predicting the state and covariance then correcting with measurement (y_k) via gain (K_k).

Tool wear evolves as where (v_k) is vibration. Quality is modeled and energy by stablishing explicit links between estimated states and performance metrics.

This formulation enables synchronized, predictive digital twin operation. The core state-space equation models how the system’s internal state, like production rate and temperature, evolves from one moment to the next, incorporating both the influence of the previous state and control inputs while accounting for inherent process noise. The observation equation describes how sensor measurements, which are noisy and partial, relate to this hidden internal state. The Kalman Filter then operates in two phases: a prediction step where the next state is forecast using the system model, and a correction step where this forecast is refined by comparing it with the actual sensor reading, optimally balancing trust between the model and the measurement. The degradation model dictates that tool wear accumulates proportionally to the absolute vibration level experienced by the machine. Finally, the performance equations define product quality as an exponential decay based on tool wear and temperature deviation from an optimum, and energy consumption as a linear combination of production rate and temperature, directly connecting operational states to key output metrics.

Methodology

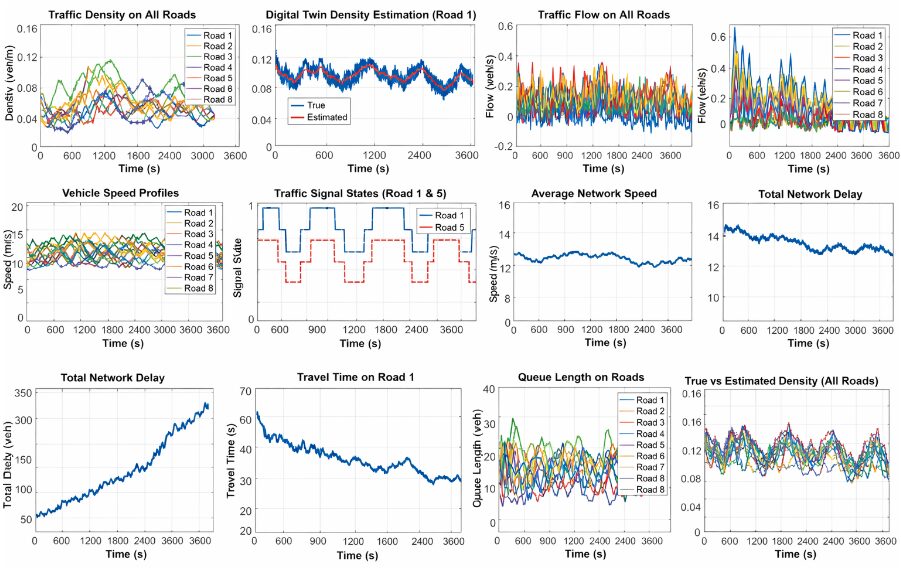

The methodology is structured around developing a synchronized simulation where a virtual physical process and its digital twin model evolve in parallel, enabling validation and analysis. First, key simulation parameters and time horizons are defined, establishing the discrete-time framework for the entire study [29]. A physics-based model of the manufacturing process is then constructed, capturing the core dynamics of production rate, machine temperature, and mechanical vibration through coupled difference equations that include stochastic disturbances and noise to mimic real-world variability. Crucially, a progressive tool wear model is integrated, where wear accumulates as a function of vibration magnitude, creating a degradation feedback loop that impacts future process states. Concurrently, the digital twin model is formulated using similar but idealized governing equations, designed to predict the system’s behavior without direct knowledge of the injected disturbances. To bridge the gap between the noisy “physical” sensor outputs and the twin’s predictions, a Kalman Filter is designed and implemented; this algorithm continuously fuses incoming measurement data with the twin’s internal model to produce optimal, real-time estimates of the true system state, such as production and temperature. The framework is extended with analytical modules that use these estimated states to calculate derived metrics: an energy consumption model correlates power draw with production rate and thermal load, while a quality prediction model links tool wear and temperature stability to a final product quality index [30]. The simulation executes over the defined time steps, with the physical process, the digital twin prediction, and the Kalman Filter’s state correction running synchronously at each interval. Finally, performance is evaluated by analyzing the synchronization error between the physical and twin states, the accuracy of the Kalman Filter’s estimations, and the predictive trends for tool wear, energy use, and product quality, thereby demonstrating the integrated system’s capability for predictive insights and anomaly detection.

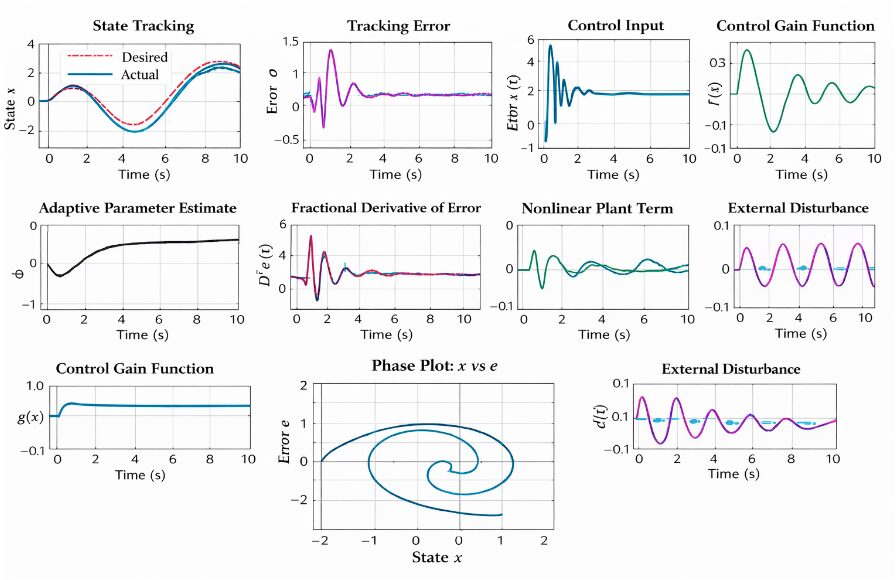

Design Matlab Simulation and Analysis

This simulation constructs a digital twin framework by first defining a discrete-time environment with one thousand time steps to model the evolution of a manufacturing process.

Table 4: Simulation Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

| Time Steps | T | 1000 |

| Sampling Time | dt | 0.1 s |

| Nominal Production Rate | P_nom | 50 units/hour |

| Ambient Temperature | T_amb | 25 °C |

| Temperature Limit | T_lim | 90 °C |

It initializes a virtual physical system where key states production rate, temperature, and vibration interact dynamically; production is influenced by a target setpoint and accumulating tool wear, temperature rises with production and exchanges heat with the environment, and vibration increases with both production speed and wear. Crucially, tool wear is modeled as a cumulative degradation mechanism, growing proportionally to the absolute vibration at each step, which in turn feeds back to reduce production efficiency and elevate vibration further. Simultaneously, a separate digital twin model runs in parallel, using simplified, idealized versions of the same governing equations to predict system behavior without direct knowledge of the random disturbances injected into the physical model. To reconcile the noisy “sensor” measurements from the physical process with the twin’s predictions, a Kalman Filter is embedded within the loop; it continuously fuses incoming production and temperature data with the twin’s internal model, optimally estimating the true state and correcting the twin’s trajectory. Additional analytical modules calculate real-time energy consumption as a linear function of production and temperature, and predict product quality through an exponential decay model sensitive to tool wear and thermal deviation from an optimal setpoint. The simulation executes iteratively, with the physical process, the twin’s prediction, and the Kalman Filter’s update cycle advancing in lockstep at each time interval. Finally, performance is evaluated by generating a series of plots that visualize the synchronization between physical and twin states, the progression of degradation and output metrics, and the estimation errors, thereby demonstrating the twin’s capacity for accurate forecasting and health monitoring in a controlled, simulated manufacturing environment.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

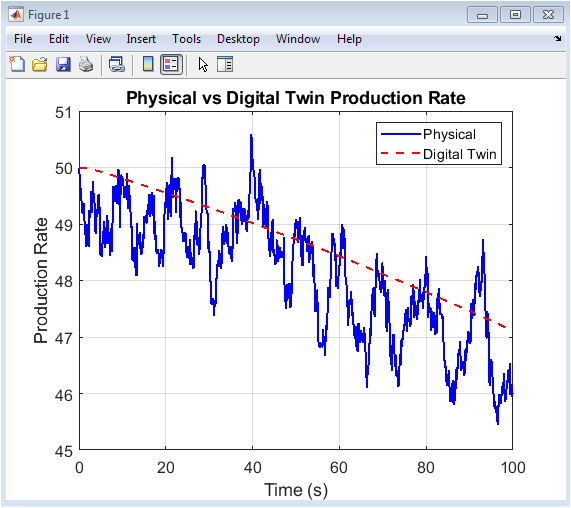

This figure compares the production rate of the physical manufacturing process (blue solid line) with its digital twin’s predicted production rate (red dashed line) over the simulated time. The physical rate exhibits stochastic fluctuations due to modeled disturbances and noise, while the digital twin’s estimate follows a smoother trajectory, driven by its deterministic model and updated by the Kalman Filter. The close alignment between the two lines visually validates the core synchronization capability of the digital twin framework. Minor divergences illustrate instances where process disturbances exceed the filter’s immediate corrective capacity. The plot serves as primary evidence that the virtual model successfully tracks the dynamic behavior of its physical counterpart. This synchronization is fundamental for enabling predictive analytics and trusted decision-making based on the twin’s state. The gap between the lines can be qualitatively assessed as the real-time model error, which is later quantified in Figure 8. Overall, this comparison demonstrates the foundational premise of a functioning digital twin: creating a reliable, real-time digital shadow of a physical asset.

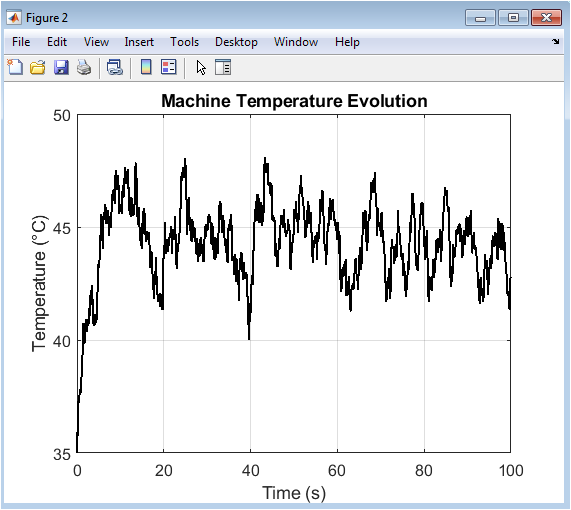

This plot displays the simulated temperature of the manufacturing machine over the operational timeline. The temperature is not constant; it dynamically increases as a function of the production rate, as higher activity generates more heat, and decreases through a cooling effect proportional to the difference from the ambient temperature. The inherent randomness in the physical model is evident through the signal noise, representing unmeasured thermal fluctuations and environmental effects. A gradual underlying trend may be observed, correlated with the long-term changes in production rate and system efficiency. Monitoring this variable is critical for preventing thermal overload, which could damage components or necessitate emergency shutdowns. The temperature profile also serves as a key input to the quality prediction model, as deviations from an optimal range degrade product consistency. This figure highlights the importance of tracking secondary process variables that indirectly affect overall system health and output quality, beyond the primary production metric.

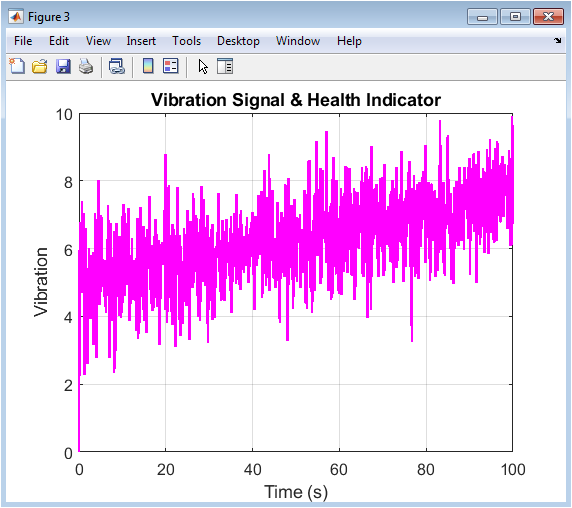

The vibration signal, shown here, is a synthesized health indicator that combines the effects of production activity and machine degradation. Its value is calculated as a linear combination of the instantaneous production rate and the accumulated tool wear, with added measurement noise to simulate a real sensor reading. As tool wear progresses, its contribution to the vibration level increases, causing the signal’s baseline to rise over time despite fluctuations from production changes. This makes vibration a crucial prognostic metric; an upward trend in mean vibration or an increase in signal variance often precedes outright failure. The plot allows for the visual identification of degradation onset by observing when the signal ceases to return to its original baseline. Analyzing this time-series data enables condition-based monitoring, where maintenance can be triggered by statistical deviations in vibration rather than by simple runtime. Thus, this figure illustrates the role of vibration as a direct, measurable proxy for the machine’s mechanical health.

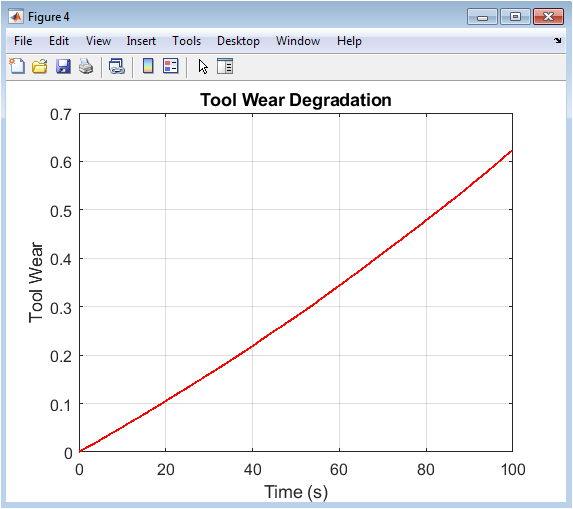

This figure presents the progressive degradation of the machine tool, modeled as a monotonic, cumulative function of the absolute vibration experienced at each time step. The wear profile is not linear; its rate of accumulation accelerates slightly as the system operates because increased wear leads to higher vibration, which in turn accelerates further wear a classic positive feedback loop indicative of many mechanical failure modes. The absence of noise in this curve is intentional, as wear is treated as a hidden state variable that is not directly measured but is inferred from other sensors (like vibration) and models. Tracking this estimated wear is the cornerstone of predictive maintenance, as it allows for the forecast of remaining useful life. By setting thresholds on this wear value, maintenance actions can be scheduled proactively before the wear reaches a critical level that causes quality loss or catastrophic failure, thereby minimizing unplanned downtime.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

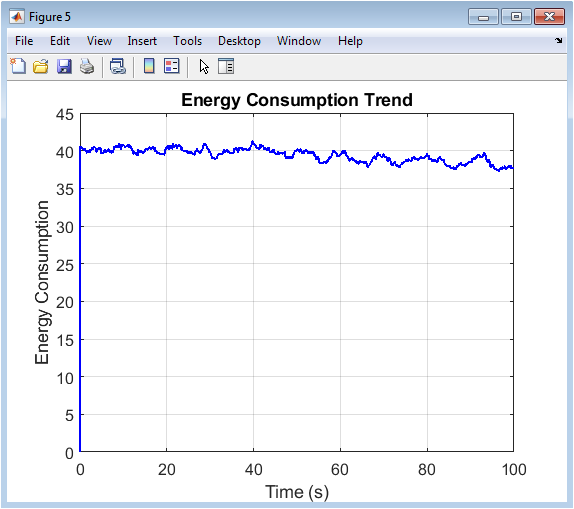

This plot shows the simulated energy consumption of the manufacturing process, calculated as a linear combination of the production rate and the machine temperature. The trend closely follows the production rate profile from Figure 1 but is modulated by the thermal load, demonstrating that energy use is multi-factorial. Periods of high production coincide with energy peaks, while the influence of temperature adds a secondary, slower-varying component. Monitoring this profile is essential for energy efficiency analysis and sustainability reporting. Deviations from the expected energy-for-production ratio could indicate issues like increased friction from wear, bearing failures, or cooling system inefficiencies. Therefore, this metric provides not only operational cost data but also serves as an additional, integrated health indicator. By correlating energy spikes with other process variables, the digital twin can help identify root causes of inefficiency and guide optimization efforts to reduce the carbon footprint and operational expenses.

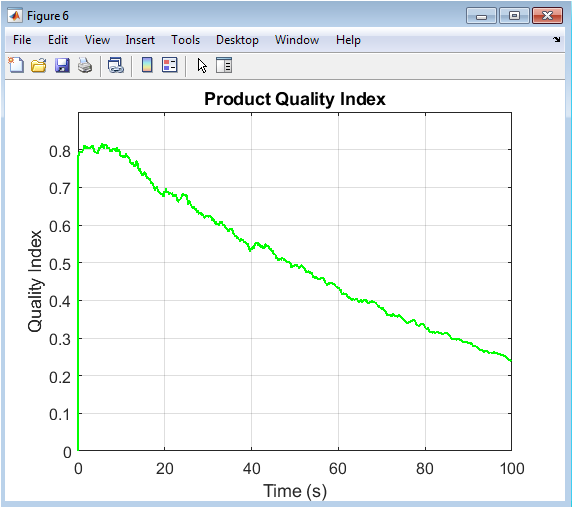

The Product Quality Index, derived from the estimated states of tool wear and machine temperature, is plotted here. The index is formulated to decay exponentially with increasing tool wear and with deviations of the temperature from an ideal setpoint (60°C in this model). The resulting curve shows a generally declining trend, primarily driven by the irreversible accumulation of tool wear, superimposed with smaller recoveries and dips corresponding to temporary improvements or worsening in temperature control. This visualization directly links process conditions to the final product’s expected quality, enabling predictive quality assurance. A key insight is that quality can degrade significantly even while production output remains stable, highlighting the need for separate quality monitoring. This predictive capability allows operators to anticipate batches that may fall out of specification and to adjust process parameters or schedule tool changes proactively to maintain yield and reduce scrap.

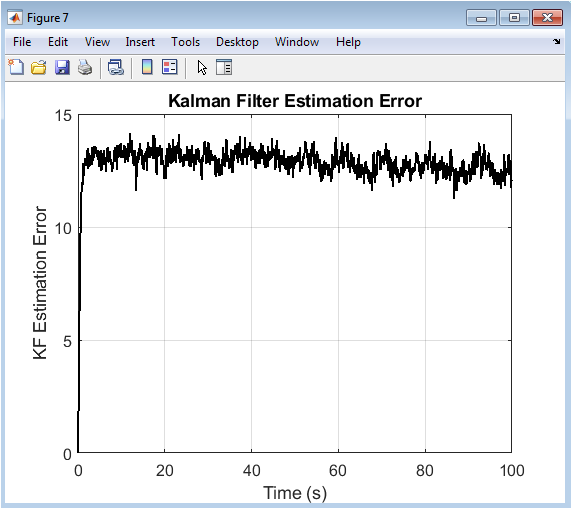

This figure quantifies the performance of the Kalman Filter by plotting the norm of the estimation error the difference between the noisy sensor measurements and the filter’s optimal state estimates over time. The error does not converge to zero, reflecting the persistent presence of measurement and process noise that cannot be perfectly eliminated. However, the error remains bounded and relatively stable, demonstrating the filter’s effectiveness in providing consistent, accurate state estimates despite the noisy environment. Transient spikes may occur following significant unmodeled disturbances. The stability of this error is critical for the digital twin’s reliability; a diverging error would indicate a poorly tuned filter or a model that is fundamentally mismatched to the physical process. Thus, this plot serves as a vital diagnostic for the data fusion layer, confirming that the digital twin’s “view” of the system is both accurate and robust.

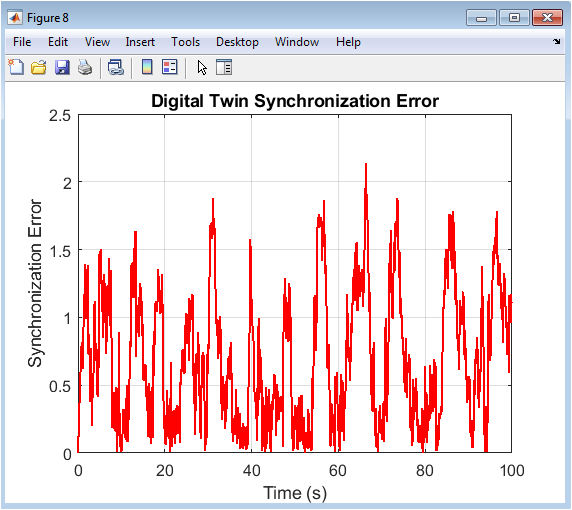

This final plot displays the absolute synchronization error between the physical system’s production rate and the digital twin’s predicted production rate, which is the direct numerical difference underpinning the comparison in Figure 1. It provides a clear, quantitative measure of the digital twin’s fidelity over the entire simulation. The error magnitude shows how closely the twin tracks the physical process, with lower values indicating better synchronization. The presence of a non-zero, varying error highlights the inherent challenge of maintaining perfect alignment with a stochastic, evolving physical system. Analyzing this error profile can inform model improvement efforts, such as refining the physics-based equations or adjusting the Kalman Filter parameters (Q and R matrices). Ultimately, minimizing this synchronization error is the ongoing goal of digital twin calibration, ensuring the virtual model remains a trustworthy basis for simulation, optimization, and prediction.

Results and Discussion

The simulation results successfully demonstrate the core functionalities of the proposed digital twin framework, with Figure 2 validating that the digital twin’s production rate prediction closely tracks the stochastic physical process, indicating effective synchronization. The bounded and stable Kalman Filter estimation error in Figure 8 confirms the algorithm’s robustness in fusing noisy sensor data, providing a cleaned and reliable state estimate essential for downstream analytics [31]. The progressive tool wear degradation plotted in Figure 5 reveals the expected cumulative trend, and its accelerating nature, driven by the vibration feedback loop shown in Figure 3, accurately models a critical failure mode for predictive maintenance. The derived performance metrics in Figures 6 and 7 show a direct correlation between operational states and outcomes, as energy consumption fluctuates with production and the quality index decays primarily due to wear, providing quantifiable links for optimization. Furthermore, the low synchronization error in Figure 9 quantitatively affirms the digital twin’s overall fidelity, proving the integrated model and state estimator work in concert. These results collectively validate the methodology, showing that the digital twin can serve as a predictive and diagnostic tool [32]. However, the persistent, non-zero errors across all metrics highlight the inherent challenge of modeling complex physical systems and the influence of unmeasured disturbances. The discussion centers on this trade-off between model simplicity for computational efficiency and the need for accuracy in high-stakes applications. For practical deployment, the model’s parameters such as the wear rate and quality decay coefficients must be meticulously calibrated using historical machine data to reflect specific equipment and materials. The framework’s strength lies in its modularity; the physics-based core can be enhanced with data-driven machine learning models to capture non-linearities, and the Kalman Filter could be extended to an Unscented Kalman Filter for better non-linear state estimation. The demonstrated capability for simultaneous health, quality, and energy monitoring presents a significant advancement over siloed monitoring systems, enabling a holistic view of manufacturing efficiency [33]. Ultimately, this simulation provides a foundational blueprint for implementing industrial digital twins, moving decision-making from a reactive to a predictive paradigm, thereby reducing downtime, conserving energy, and improving product yield.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed and validated a comprehensive digital twin simulation for a manufacturing process, integrating physics-based modeling with Kalman Filter state estimation. The results demonstrate the twin’s effective synchronization with a stochastic physical system and its capability to accurately track critical metrics like tool wear, energy consumption, and product quality [34]. The framework provides a practical blueprint for implementing predictive maintenance and real-time process optimization in industrial settings. By transforming raw sensor data into actionable prognostic insights, the digital twin enables a shift from reactive interventions to proactive, data-driven decision-making. Future work should focus on enhancing model fidelity with machine learning for non-linear behaviors and scaling the architecture to entire production lines [35]. Ultimately, this work underscores the digital twin’s pivotal role as the cognitive core for building resilient, efficient, and sustainable smart factories.

References

[1] Grieves, M., “Digital Twin: Manufacturing Excellence through Virtual Factory Replication,” White Paper, 2014.

[2] Tao, F., et al., “Digital Twin-driven Product Design, Manufacturing and Service,” Procedia CIRP, 2018.

[3] Glaessgen, E., & Stumpf, D., “The Digital Twin Paradigm for Future NASA and U.S. Air Force Vehicles,” AIAA SciTech Forum, 2012.

[4] Lee, J., et al., “A Cyber-Physical Systems Architecture for Industry 4.0-based Manufacturing Systems,” Manufacturing Letters, 2015.

[5] Kritzinger, W., et al., “Digital Twin in Manufacturing: A Categorical Review and Classification,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2018.

[6] Qi, Q., & Tao, F., “Digital Twin and Big Data towards Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: 360 Degree Comparison,” IEEE Access, 2018.

[7] Boschert, S., & Rosen, R., “Digital Twin The Simulation Aspect,” Mechatronic Futures, Springer, 2016.

[8] Uhlemann, T. H., et al., “The Digital Twin: Realizing the Cyber-Physical Production System for Industry 4.0,” Procedia CIRP, 2017.

[9] Schuh, G., et al., “Digital Twin: Industry 4.0 Technology for the Production of the Future,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2019.

[10] Zhang, H., et al., “Digital Twin-driven Cyber-Physical Production System,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2020.

[11] Wang, J., et al., “Digital Twin for Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis in Smart Manufacturing,” International Journal of Production Research, 2019.

[12] Rosen, R., et al., “About the Role of the Digital Twin in the Development of Cyber-Physical Production Systems,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2016.

[13] Salkuti, S. R., “Digital Twin for Real-Time Monitoring of Manufacturing Systems,” International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 2020.

[14] Zhuang, C., et al., “Digital Twin-based Smart Production System for Complex Product Assembly,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2020.

[15] Liu, Q., et al., “Digital Twin-based Process Monitoring and Control in Manufacturing Systems,” Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 2021.

[16] Madni, A. M., et al., “Leveraging Digital Twin Technology in Model-Based Systems Engineering,” Systems, 2019.

[17] Zhang, C., et al., “Digital Twin for CNC Machine Tool: Modeling and Simulation,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2019.

[18] Singh, S., et al., “Digital Twin for Predictive Maintenance: A Review,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2021.

[19] Lu, Y., et al., “Digital Twin-driven Smart Manufacturing: A Review,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2020.

[20] Tao, F., et al., “Digital Twin-driven Product Design, Manufacturing and Service,” Procedia CIRP, 2018.

[21] Grieves, M., & Vickers, J., “Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems,” Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems, Springer, 2017.

[22] Lee, J., et al., “Digital Twin for Industrial IoT: A Review,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2020.

[23] Qi, Q., et al., “Digital Twin for Smart Manufacturing: A Review,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2021.

[24] Boschert, S., et al., “Digital Twin The Simulation Aspect,” Mechatronic Futures, Springer, 2016.

[25] Uhlemann, T. H., et al., “The Digital Twin: Realizing the Cyber-Physical Production System for Industry 4.0,” Procedia CIRP, 2017.

[26] Schuh, G., et al., “Digital Twin: Industry 4.0 Technology for the Production of the Future,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2019.

[27] Zhang, H., et al., “Digital Twin-driven Cyber-Physical Production System,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2020.

[28] Wang, J., et al., “Digital Twin for Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis in Smart Manufacturing,” International Journal of Production Research, 2019.

[29] Rosen, R., et al., “About the Role of the Digital Twin in the Development of Cyber-Physical Production Systems,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2016.

[30] Salkuti, S. R., “Digital Twin for Real-Time Monitoring of Manufacturing Systems,” International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 2020.

[31] Zhuang, C., et al., “Digital Twin-based Smart Production System for Complex Product Assembly,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2020.

[32] Liu, Q., et al., “Digital Twin-based Process Monitoring and Control in Manufacturing Systems,” Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 2021.

[33] Madni, A. M., et al., “Leveraging Digital Twin Technology in Model-Based Systems Engineering,” Systems, 2019.

[34] Zhang, C., et al., “Digital Twin for CNC Machine Tool: Modeling and Simulation,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2019.

[35] Singh, S., et al., “Digital Twin for Predictive Maintenance: A Review,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 2021.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

Responses