Renewable Energy Policies in the European Union: Germany Example, Legal Regulations and Alternative Energy Sources

Introduction

Global climate change is the greatest problem facing the world. While countries are taking measures to secure energy independence, they must not overlook global climate change. To this end, in addition to the 1987 Montreal Protocol, the Kigali Amendment was signed in 2016. With the Kigali Amendment, climate targets were set to gradually reduce hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). Particularly after the Kigali Amendment, the policies of the European Union—and especially those of Germany in recent years—have centered on combating global climate change and ensuring energy security. In pursuit of this goal, the European Union has set a target of carbon neutrality by 2050 [1]. The Russia-Ukraine war in 2022 turned the EU’s energy dependency into a major problem. In 2020, 45% of the EU’s total natural gas imports came from Russia, while for Germany this rate reached 55% [2]. This study examines the legal regulations regarding renewable energy in Germany and the EU following the Kigali Protocol, with a particular focus on alternative approaches for achieving energy independence.

Historical Development of Legal Regulations

In September 2010, approximately six months before the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Germany published its energy transition policy (Energiewende). This policy aimed to move away from fossil fuels. After the 2016 Kigali Amendment, the process continued throughout the entire European Union [3]. Following the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, more stringent measures were implemented, such as increasing the incentives for heat pumps.

In 2021, the Renewable Energy Sources Act was published and later revised in 2023. Initially, the goal was to use entirely renewable sources with targets of 65% by 2030 and 100% by 2045; however, the 2030 target was raised to 80% [4]. In 2022, the annual solar energy installation target of 7.5 GW was increased to 9 GW in 2023. Legal regulations permitting agro-photovoltaic systems on agricultural lands were also introduced [5].

In the 2023 amendment, fossil fuel-based heating systems were banned in new buildings. Starting in 2024, existing buildings will also be required to replace coal and oil-fired boilers. Subsidies for heat pumps were increased from 40% to 50%. With the sale of 236,000 heat pumps in 2022, Germany became the leader in Europe [4], [6].

A law passed in 2020 originally envisaged the closure of coal power plants by 2038, but this target was brought forward to 2030. In this context, 15 coal power plants were shut down early in 2023 (Agora Energiewende 2023). In 2023, the national hydrogen strategy was updated, raising the target for electrolyzer capacity from 10 GW to 20 GW by 2030. It also aimed to accelerate the transition to green hydrogen in the steel and chemical sectors [7], [8].

Alternative Energy Sources

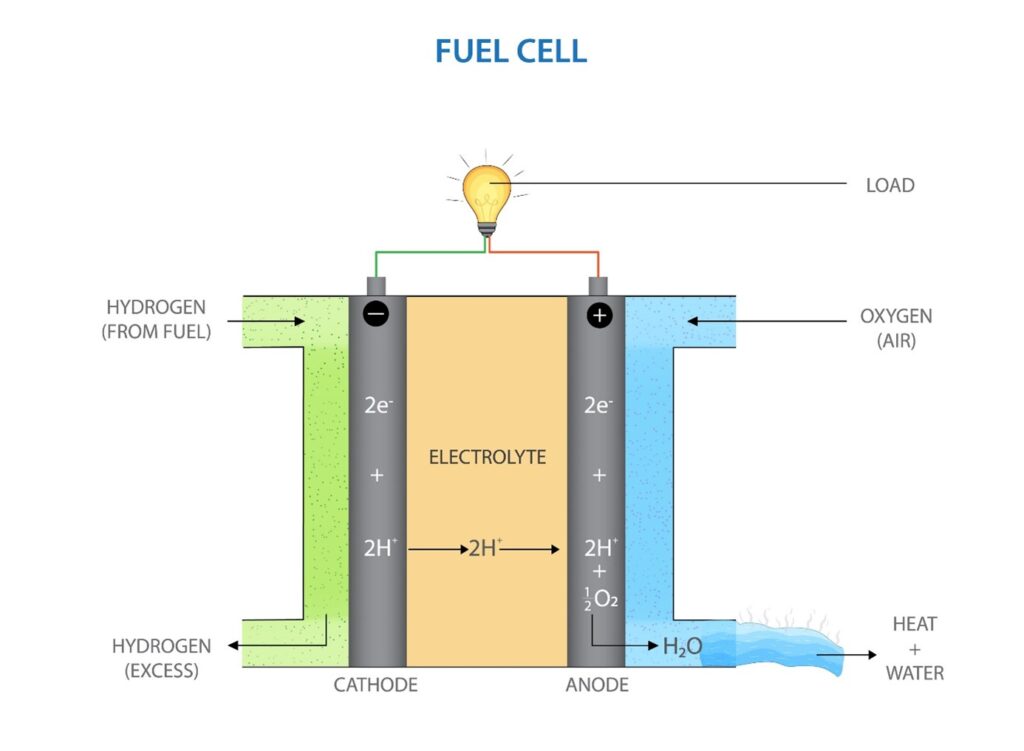

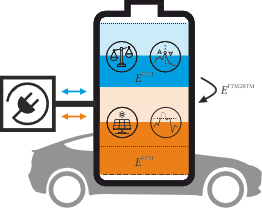

Electrolyzer and Fuel Cell

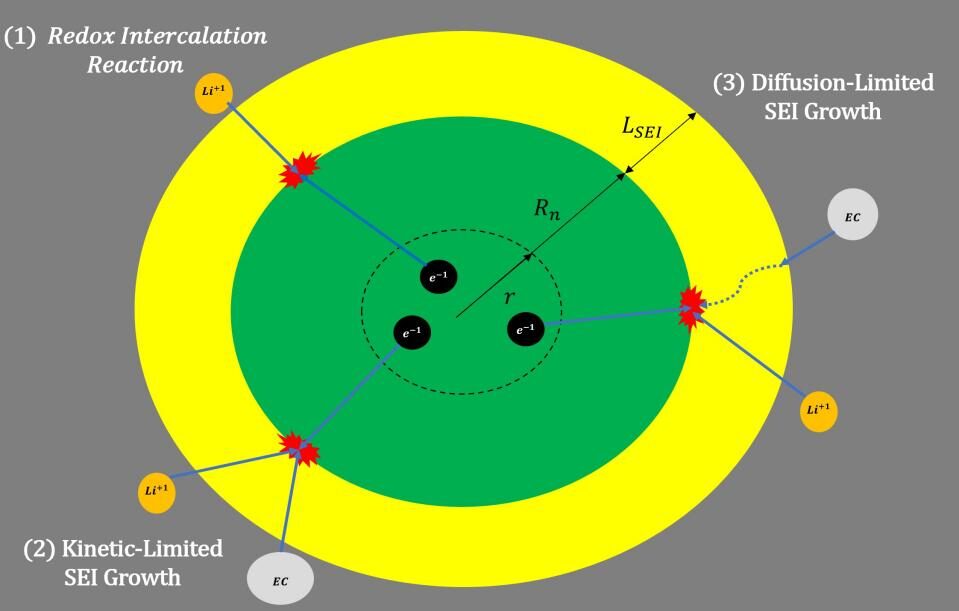

In our era, where electric cars and electronic devices are becoming increasingly common, battery technologies are used to store and safely utilize electrical energy. Batteries, which require large amounts of electricity, are particularly essential for electric cars. Currently, lithium batteries are the preferred method. However, the controversies surrounding lithium batteries have brought fuel cell technology using hydrogen to the forefront. The use of cobalt—obtained under poor and unhealthy conditions by child labor in the Congo—and the environmental damage caused during cobalt extraction have ultimately led to a decline in the popularity of lithium batteries [9]–[11]. Hydrogen is emerging as an environmentally friendly alternative in the energy transition. Since hydrogen combustion produces only water vapor, it plays a critical role in reducing the carbon footprint. Green hydrogen is produced by the electrolysis of water using electricity generated from renewable energy sources, making the production process nearly zero-emission [12].

Electrolyzers are devices used to separate water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Their operating principles are based on electrochemical reactions. Essentially, two main types of electrolyzers stand out: alkaline electrolyzers and proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers.

- Alkaline electrolyzers: In these devices, alkaline solutions such as potassium hydroxide are commonly used. Within the cell, water molecules are dissociated through the movement of ions between the electrodes. This technology is relatively low-cost and durable, but it exhibits less flexibility under dynamic operating conditions.

- PEM electrolyzers: In this technology, the use of a proton exchange membrane provides higher efficiency and a faster response time. PEM systems are preferred particularly for their suitability in integrating with fluctuating renewable energy sources.

Both technologies play a key role in the future green energy transition and hold an important place in Germany’s national hydrogen strategy [5], [12], [13].

Figure 1. Working Principle of PEMFC [13].

Heat Pumps

The operating principles of heat pumps are no different from those of car air conditioners, household refrigerators, or domestic air conditioners. They use a vapor compression cooling cycle from a thermodynamic perspective. In refrigerators, the evaporator absorbs the energy from the contents inside—causing the special refrigerant to evaporate—while the heat is expelled through the coils at the back (condenser). A classic thermodynamics question is: when you leave a refrigerator door open, does the room get colder? People who experience an instantaneous cool sensation when the door is opened might answer “yes,” but the net heat released into the room is greater than the cooling effect due to the heat consumed by the compressor. It is precisely this principle that heat pumps operate on. The heat released at the condenser is what warms our homes.

There are three types of heat pumps: air-source, ground-source, and water-source. Heat pumps are especially noted for their energy efficiency and low operating costs.

- Air-source heat pumps: They draw heat from the ambient air, are easier to install, but their performance may vary depending on external conditions.

- Ground-source pumps: They offer high efficiency by taking advantage of the stable temperature of the ground, although their installation costs are high.

The European Union and Germany are implementing various legal regulations and financial incentives to promote the widespread adoption of heat pumps. In Germany, especially within the framework of the “Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz” (EEG), subsidies provided for the integration of renewable energy sources and energy efficiency projects support investments in heat pumps. In Europe, regulations such as the “Energy Performance of Buildings Directive” (EPBD) mandate improved energy efficiency in buildings and the use of low-carbon heating systems. These regulations provide legal certainty for the use and integration of heat pumps [14].

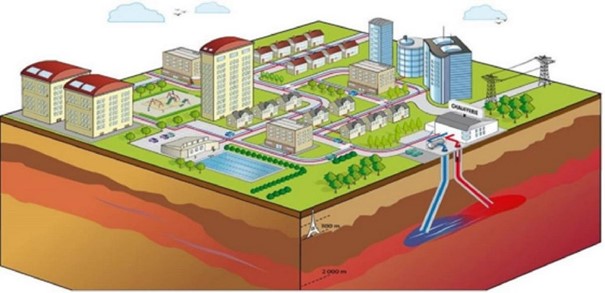

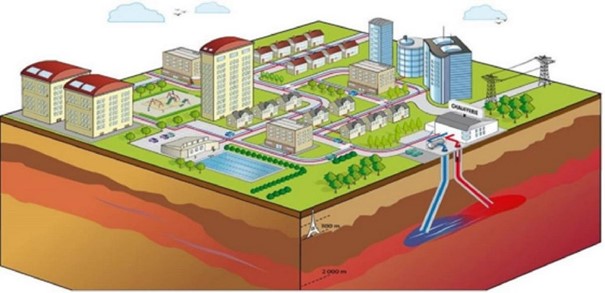

Geothermal Cities

Geothermal energy is the heat energy obtained from deep within the Earth’s crust. This energy is used directly in heating systems and power generation facilities. Geothermal energy systems operate using technologies such as drilling and closed-loop heat exchange systems. As a renewable and environmentally friendly resource, geothermal energy not only meets our energy needs but also helps protect our environment. In particular, deep geothermal systems, due to their high heat potential, are promising in terms of energy efficiency. Although geothermal energy is not yet widely used in Germany, there are some pilot projects and local applications. For example, the deep geothermal project conducted by the Canadian company Eavor in Geretsried serves as a pilot application to meet the city’s energy needs. This project has demonstrated the success of extracting heat from deep below the surface by integrating standard drilling techniques with innovative magnetic guidance systems [15], [16].

Figure 2 geothermal power plant [17]

In France, particularly in the Paris region, geothermal energy is widely used in urban heating networks. Additionally, Larderello in Italy is one of the pioneering examples in geothermal power generation [17].

Unlike other renewable sources such as wind and solar, geothermal energy is a predictable and reliable energy source that is not affected by weather conditions or seasonal changes. When integrated with organic Rankine cycles and other heat recovery systems, the potential for establishing geothermal cities with geothermal energy is always present [18]–[20].

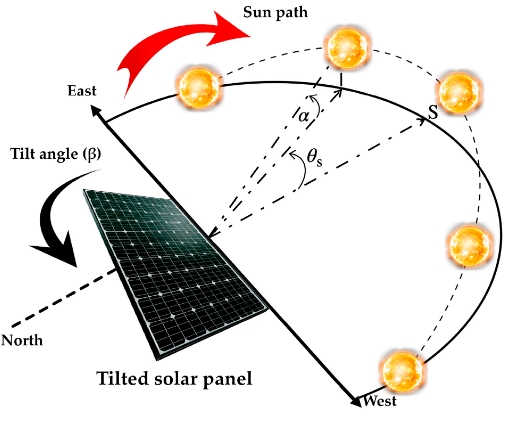

Solar and Wind Energy

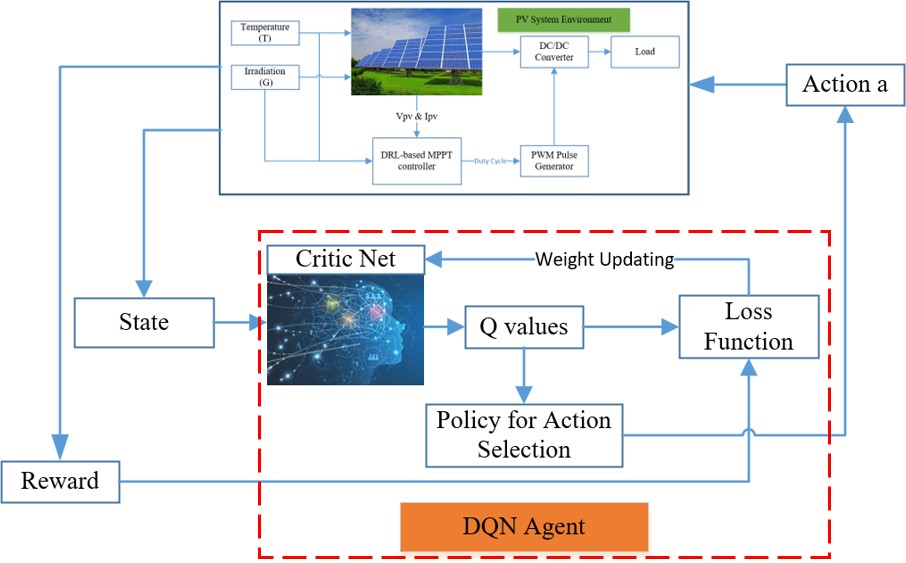

Solar energy enables the generation of electricity from sunlight through photovoltaic panels. The production of photovoltaic cells from semiconductor materials relies on a semiconductor reaction that converts photons in sunlight into electricity. This technology is widely implemented due to its modular structure and low operating costs.

Germany has long been an important market for photovoltaic technologies, taking significant steps in terms of technological innovation and cost optimization. The integration of phase change materials helps reduce the peak loads of photovoltaic panels. The use of robotic and control systems for sun tracking and dust cleaning ensures efficient utilization of solar energy. Energy storage with phase change materials, particularly in solar water heating systems, allows solar energy to be used as a power source during nighttime when there is no sunlight. In this respect, the potential of solar energy remains an inexhaustible alternative [21]–[23].

Wind energy is based on the principle of converting kinetic energy into electrical energy. Wind turbines convert the kinetic energy of wind into mechanical energy through their aerodynamic design and mechanical transmission, and then into electrical energy via generators.

Both onshore and offshore wind farms constitute a significant portion of energy production in Germany and throughout Europe. Germany’s wind energy capacity is especially concentrated in the northern regions, and technological and legal developments in this field are continuously being monitored [14], [24].

The promotion of solar and wind energy is significantly supported by the legal regulations of the European Union and Germany. Germany’s EEG (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz) law prioritizes renewable energy sources and offers attractive incentive packages for investors. Additionally, EU regulations such as the “Renewable Energy Directive” mandate the use of renewable energy in member states and support market integration. These legal frameworks not only ensure market stability but also promote technological developments and secure the financial sustainability of renewable energy projects [14].

Conclusion

Europe’s, and particularly Germany’s, energy transition is supported not only by technological innovations but also by comprehensive legal regulations and strategic policies. Hydrogen energy, heat pumps, geothermal energy, solar and wind energy, and fuel cells constitute the cornerstones of sustainable and low-carbon energy systems.

In the realm of hydrogen energy, the development of electrolyzer technologies plays a critical role in the production of green hydrogen, while the relevant legal regulations support the scalability and economic viability of this technology. Heat pumps increase energy efficiency in buildings and facilitate the integration of renewable energy; laws such as Germany’s EEG provide incentive mechanisms for these technologies. Geothermal energy offers an alternative solution for meeting the energy needs of cities with its deep technological infrastructure and environmentally friendly applications, although expanding its use requires flexibility and innovation in legal regulations.

Solar and wind energy form the backbone of Europe’s renewable energy portfolio, and both the technical and legal infrastructures supporting the widespread adoption of these technologies are continually being developed. Fuel cells, on the other hand, have gained attention as an alternative to fossil fuels, particularly in transportation and industrial applications, and are supported by corresponding legal regulations.

The strategic objectives set by Europe for next-generation renewable energy technologies encompass both technical innovations and legal regulations. Germany’s national strategies serve as an example in supporting domestic production and technological independence, while also aligning with Europe’s overall energy policy. In this context, given the rapid pace of technological advancements today, the flexibility of legal regulations, cost-effectiveness, and ensuring market stability are of great importance.

In conclusion, the synergy between the technical, economic, and legal dimensions of renewable energy technologies in the energy transition process in Europe and Germany is critical for a sustainable future. Through cooperation between the public and private sectors, supporting technological innovations with legal frameworks will facilitate the development of competitive and environmentally friendly solutions in the energy market. In the future, the broader implementation of these technologies will take important steps toward reducing carbon emissions and ensuring energy supply security. In line with the strategic objectives set by Europe and Germany, the integration of renewable energy technologies will contribute both to economic growth and environmental sustainability.

References

[1] Undep.org, “About Montreal Protocol.” https://www.unep.org/ozonaction/who-we-are/about-montreal-protocol#:~:text=The Parties to the Montreal,cent by the late 2040s.

[2] IEA, “Germany 2020 Energy Policy Review,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/60434f12-7891-4469-b3e4-1e82ff898212/Germany_2020_Energy_Policy_Review.pdf

[3] Energiewende-global.com, “Energy in Transition-Powering Tomorrow.” https://energiewende-global.com/en/

[4] BMWK, “Renewable Energy,” 2025. https://www.bmwk-energiewende.de/EWD/Redaktion/EN/Newsletter/2022/07/Meldung/news2.html#:~:text=Its guidelines for the expansion,will fall under regular funding.

[5] Fraunhofer ISE, “Public Net Electricity Generation 2023 in Germany: Renewables Cover the Majority of the Electricity Consumption for the First Time,” 2024. https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/press-media/press-releases/2024/public-electricity-generation-2023-renewable-energies-cover-the-majority-of-german-electricity-consumption-for-the-first-time.html

[6] BDEW, “Stadtwerkestudie 2023,” 2024. https://www.bdew.de/energie/stadtwerkestudie-2023/

[7] A. Energiewende, “Kohleaussteig,” 2024. https://www.agora-energiewende.de/themen/kohleausstieg/related/tab-1/page/1

[8] European Parliament, “Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’),” Off. J. Eur. Union, vol. 64, no. 7, pp. 1–17, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2021:243:FULL&from=EN

[9] L. Mucha, “Kongo: Der Preis der Kobltgier,” Deutsche Welle, 2018. https://www.dw.com/de/kongo-der-preis-der-kobaltgier/g-43916245

[10] S. Schlindwein, “Kleinbergbau als Chance?,” Kobalt aus dem Kongo, 2023. https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/kobalt-aus-dem-kongo-100.html

[11] L. Staude, “Kobaltabbau im Kongo Der hohe Preis für Elektroautos und Smartphones,” 2019. https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/kobaltabbau-im-kongo-der-hohe-preis-fuer-elektroautos-und-100.html

[12] B. Spencer, “Do Labour’s hopes of a hydrogen driven future hold water?,” 2024. https://www.thetimes.com/uk/article/do-labours-hopes-of-a-hydrogen-driven-future-hold-water-n2cnzxzwv?region=global

[13] S. Lauren, “What are proton exchange membrane fuel cell and how do they work?,” 2024. https://www.biolinscientific.com/blog/what-are-proton-exchange-membrane-fuel-cells-and-how-do-they-work

[14] A. Pecout, “Techologies propres,” 2024. https://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2024/10/16/technologies-propres-le-constat-d-un-defaut-de-strategie-industrielle-europeenne_6353441_3234.html

[15] D. Wetzel, “Unerschöpflich und sauber – Der entscheidende Durchbruch für Deutschlands Energie-Traum,” 2024. https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/plus253634352/Energie-Unerschoepflich-und-sauber-Entscheidender-Durchbruch-fuer-Deutschlands-Erdwaerme-Traum.html

[16] P. Bayer, G. Attard, P. Blum, and K. Menberg, “The geothermal potential of cities,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 106, pp. 17–30, May 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.02.019.

[17] A. Richer, “Geothermal energy has its place in the energy mix, since it overcomes the shortcomings of other renewable sources, mainly intermittent, such as wind or solar.,” 2021. https://www.thinkgeoenergy.com/geothermal-energy-source-of-heat-cold-and-electricity/

[18] A. McClean and O. W. Pedersen, “The role of regulation in geothermal energy in the UK,” Energy Policy, vol. 173, p. 113378, Feb. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113378.

[19] A. Schuster, S. Karellas, E. Kakaras, and H. Spliethoff, “Energetic and economic investigation of Organic Rankine Cycle applications,” Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 29, no. 8–9, pp. 1809–1817, 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2008.08.016.

[20] I. Encabo Cáceres, R. Agromayor, and L. O. Nord, “Thermodynamic Optimization Of An Organic Rankine Cycle For Power Generation From A Low Temperature Geothermal Heat Source,” Proc. 58th Conf. Simul. Model. (SIMS 58) Reykjavik, Iceland, Sept. 25th – 27th, 2017, vol. 138, pp. 251–262, 2017, doi: 10.3384/ecp17138251.

[21] J. Bony and S. Citherlet, “Numerical model and experimental validation of heat storage with phase change materials,” Energy Build., vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 1065–1072, 2007, doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2006.10.017.

[22] T. Rozenfeld, Y. Kozak, R. Hayat, and G. Ziskind, “Close-contact melting in a horizontal cylindrical enclosure with longitudinal plate fins: Demonstration, modeling and application to thermal storage,” Int. J. Heat Mass Transf., vol. 86, pp. 465–477, 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2015.02.064.

[23] L. F. Cabeza, Advances in Thermal Energy Storage Systems. Elsevier, 2015. doi: 10.1016/C2013-0-16453-7.

[24] F. Besnard and L. Bertling, “An approach for condition-based maintenance optimization applied to wind turbine blades,” IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 77–83, 2010, doi: 10.1109/TSTE.2010.2049452.

Responses