A MATLAB Simulation Platform for Testing Autonomous Navigation Algorithms in Dynamic Environments

Author : Waqas Javaid

Abstract

This paper presents a comprehensive MATLAB-based simulation framework for autonomous vehicle navigation, integrating path planning, vehicle dynamics, and sensor simulation. We implement a complete system using the A algorithm for optimal path planning in obstacle-rich 2D environments, coupled with a kinematic vehicle model for realistic motion simulation. The framework incorporates lidar sensor simulation for real-time obstacle detection with configurable range and resolution [1]. A PID-based control system governs both steering and speed for precise path following. The system architecture includes environment generation with random obstacles, occupancy grid mapping, and multi-sensor data fusion. Experimental results demonstrate successful navigation from start to goal while avoiding collisions through continuous lidar monitoring [2]. We provide complete trajectory logging and performance analysis across steering, speed, and safety metrics. The modular implementation serves as an effective platform for testing autonomous navigation algorithms without requiring physical hardware [3]. This work contributes a practical, open-source simulation tool for research and education in autonomous vehicle technologies.

Introduction

The rapid advancement of autonomous vehicle technology necessitates robust and reliable navigation systems capable of operating in complex, dynamic environments.

These systems must integrate several core functionalities: perceiving the environment, planning a safe and efficient path, and executing precise vehicle control. Developing and testing such integrated systems on physical hardware is often costly, time-consuming, and poses significant safety risks [4]. Consequently, high-fidelity simulation platforms have become indispensable tools for research, prototyping, and validation. This paper addresses this need by presenting a comprehensive, modular simulation framework for autonomous navigation, entirely implemented in MATLAB. Our framework constructs a simulated 2D world populated with static obstacles and defines a navigation task from a start point to a goal.

Table 1: Environment Parameters

| Parameter | Value |

| Environment Size | 100 × 100 |

| Number of Obstacles | 20 |

| Obstacle Radius | 2 m |

| Start Position | (5, 5) |

| Goal Position | (95, 90) |

| Grid Resolution | 1 m |

At its core, the system employs the A* search algorithm to compute an optimal, collision-free path over an occupancy grid representation of the environment [5]. To bring this plan to life, we simulate a vehicle with kinematic bicycle dynamics, whose motion is governed by a Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller for both steering and speed regulation. A simulated lidar sensor provides the vehicle with a 360-degree perception capability, enabling real-time obstacle detection and enriching the simulation’s realism [6]. By logging all states and control signals, the framework allows for detailed analysis of navigation performance, including path-tracking accuracy and safety margins [7]. This integrated approach, combining planning, control, and sensing into a single testbed, provides a valuable platform for algorithm development, educational demonstration, and preliminary validation of autonomous navigation strategies before their deployment on physical vehicles.

1.1 The Proposed Integrated Solution

Our proposed solution is a complete, modular simulation framework that methodically addresses each layer of the autonomous navigation stack. The process begins with the generation of a configurable 2D environment featuring static obstacles, within which a start point and a goal location are defined. For the crucial task of path planning, we implement the A* search algorithm, a widely-used and optimal graph-search method, to compute the shortest collision-free route over a discrete occupancy grid. To transform this planned path into physical motion, we model the vehicle using a kinematic bicycle model, which provides a mathematically tractable yet realistic representation of a car’s steering and velocity dynamics. The execution of the path is managed by a Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control system, which calculates the necessary steering angle and forward speed to minimize the error between the vehicle’s current position and its target waypoint [8]. Furthermore, to introduce a critical layer of environmental awareness, we simulate a rotating lidar sensor that provides 360-degree distance measurements, mimicking real-world perception and enabling the monitoring of obstacle proximity [9]. The entire simulation operates in a closed loop: the vehicle state is updated based on control inputs, new sensor data is generated, and the controller continuously corrects the trajectory. All system variables including position, speed, steering commands, and sensor readings are meticulously logged for post-process analysis of performance metrics like tracking accuracy and minimum obstacle distance [10]. This end-to-end approach not only demonstrates a functional navigation pipeline but also provides a versatile and accessible testbed for experimenting with different algorithms in planning, control, and perception, thereby forming a solid foundation for future research and development in autonomous systems.

1.2 Technical Implementation and System Architecture

The technical implementation details the systematic construction of each module within the MATLAB environment. We begin by programmatically defining the operational workspace a two-dimensional Cartesian plane with boundaries and a user-specified number of circular obstacles randomly distributed to create a complex, unstructured scenario. An occupancy grid is then generated from this world model, discretizing the continuous space into searchable cells marked as free or occupied, which serves as the foundational map for the path planner [11]. The A* algorithm operates on this grid, utilizing a cost function that combines the actual distance traveled from the start node with a heuristic estimate (typically Euclidean distance) to the goal, ensuring an optimal and efficient search. The output is an ordered sequence of discrete grid waypoints, which are subsequently converted back into a continuous global path for the vehicle to follow. Concurrently, the vehicle model is initialized with parameters like wheelbase and maximum speed, and its state defined by position and heading is set to the global start coordinates. The sensor model is configured with key specifications such as maximum detection range and angular resolution, defining its perceptual field [12]. This structured, layer-by-layer architecture ensures that each component of the system is clearly defined, modular, and capable of being independently modified or upgraded for specific experimental needs.

1.3 The Navigation Loop and Performance Analysis

The core of the simulation is the dynamic navigation loop, where planning transitions into real-time execution and continuous feedback. This loop iterates at a fixed time step, with each cycle performing a sequence of critical operations.

Table 2: Vehicle and Control Parameters

| Parameter | Value |

| Time Step (dt) | 0.1 s |

| Wheelbase (L) | 2.5 m |

| Maximum Speed | 5 m/s |

| Steering Gain (Kp) | 1.0 |

| Speed Gain (Kp) | 1.0 |

The controller calculates the bearing to the immediate target waypoint on the pre-computed path and determines the steering command required to align the vehicle’s heading with this direction. Simultaneously, a separate control law adjusts the forward speed, often proportional to the distance to the target, to ensure smooth approach and halt [13]. These actuator commands are fed into the kinematic model equations, which update the vehicle’s state (x, y, theta) for the next time instant, simulating physical movement. The virtual lidar is then “fired” from this new position, casting rays at discrete angles to calculate distances to the nearest obstacles, effectively simulating a proximity scan of the local environment. The system continuously checks if the current waypoint has been reached within a tolerance and, if so, advances the target to the next point along the path. Throughout this process, a comprehensive suite of data including the full trajectory, all control inputs, and the minimum detected obstacle distance is recorded into log arrays. This rich dataset enables a multi-faceted post-simulation performance analysis, allowing us to plot the actual driven trajectory against the planned path, visualize control effort over time, and assess safety margins through obstacle proximity plots, providing a complete picture of the system’s behavior and efficacy.

1.4 Contribution and Application

The primary contribution of this work is the delivery of a fully integrated, open-source simulation testbed that encapsulates the complete autonomy pipeline within a single, coherent MATLAB script. It demonstrates a practical and pedagogical bridge between theoretical algorithms such as graph search for planning and PID for control and their tangible effects in a simulated robotic system. The framework serves multiple valuable purposes: it is an effective educational tool for students in robotics and control engineering to understand system integration, a rapid prototyping platform for researchers to test new planning or control algorithms against a standard baseline, and a validation environment for verifying fundamental navigation logic before committing to expensive hardware trials [14]. By making the complete code and methodology available, we lower the barrier to entry for experimentation in autonomous navigation. Future extensions of this work are readily conceivable, including the introduction of dynamic obstacles, integration of more advanced sensor models like cameras, implementation of sophisticated control strategies like Model Predictive Control (MPC), or the use of the framework as a training environment for machine learning-based navigation policies [15]. Thus, this simulation represents not just a standalone demonstration, but a foundational and extensible platform for ongoing innovation in the field of autonomous vehicle research.

Problem Statement

Developing a reliable and safe autonomous vehicle navigation system presents a multi-faceted engineering challenge that requires the seamless integration of several interdependent components. The core problem involves creating a cohesive software framework that can generate and interpret a map of a static environment containing obstacles plan a globally optimal and collision-free path from a start to a goal location execute this plan by generating precise low-level control signals for vehicle steering and acceleration. Furthermore, the system must incorporate simulated perception, such as lidar, to monitor the environment in real-time, adding a layer of validation and realism. Testing such integrated systems on physical vehicles is prohibitively expensive, risky, and inefficient for initial algorithm development and iteration. Therefore, there is a significant need for a comprehensive yet accessible simulation platform that models the entire navigation stack from environmental representation and path planning to vehicle dynamics and sensor feedback within a single, modular, and analyzable environment. This platform must allow for the isolated testing of individual components (like the path planner or controller) as well as the evaluation of their combined performance, providing clear metrics for success and failure before any real-world deployment.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

Mathematical Approach

The system’s mathematical foundation rests on three core formulations. Path planning is formalized through the A* algorithm’s cost function:

f(n) = g(n) + h(n)

Where g(n) is the exact cost from the start node and h(n) is the admissible heuristic to the goal. Vehicle motion is governed by the kinematic bicycle model:

ẋ = v cos(θ),

ẏ = v sin(θ),

θ̇ = (v / L) tan(δ)

Relating velocity (v) and steering angle (δ) to pose. Control is achieved via proportional (P) laws for steering, and speed to track waypoints

δ = K (θ_des – θ)

v = min(v_max, K d)

Sensor perception is modeled with ray-casting, calculating intersection points between parametric ray equations and circular obstacle boundaries. The mathematical model for path planning uses an algorithm that calculates the total estimated cost to reach the goal by summing two values. the actual cost of the path traveled from the start point, and an optimistic straight-line distance estimate to the destination. For vehicle movement, we use a simplified car model where the change in horizontal position depends on the speed multiplied by the cosine of the heading angle. Similarly, the vertical position change depends on the speed multiplied by the sine of the heading angle. The vehicle’s turning rate is determined by dividing its speed by the wheelbase length, then multiplying by the tangent of the steering angle. Steering control operates by calculating the difference between the desired direction toward the target and the current heading, then multiplying this error by a proportional gain factor. Speed control uses another proportional law that sets velocity proportional to the distance to the target, while respecting a maximum speed limit. The lidar sensor simulation works by mathematically projecting rays from the vehicle at various angles and calculating their intersection with circular obstacle boundaries. Each ray’s path is represented parametrically as a line extending from the vehicle position at a specific angle. The system solves for the distance at which this line first intersects any obstacle circle using distance formulas, providing simulated range measurements. These equations together create a closed-loop system where planned paths generate target points, control laws convert position errors into steering and speed commands, the kinematic model translates these commands into new positions, and sensor models validate safety by detecting nearby obstacles. This integrated mathematical framework enables the complete simulation of autonomous navigation from high-level planning to low-level actuation.

Methodology

The methodology for building the autonomous navigation simulator follows a systematic, modular pipeline, beginning with environmental modeling. A two-dimensional operational workspace is defined, within which circular obstacles are randomly generated to create a complex, static scenario for testing. The continuous space is then discretized into an occupancy grid map, where each cell is labeled as free or occupied based on its proximity to obstacles, forming the searchable domain for the path planner [16]. The core navigation path is computed using the A* graph search algorithm, which finds the optimal, collision-free sequence of grid cells from the specified start point to the goal by minimizing a combined cost of distance traveled and estimated remaining distance. This discrete path is subsequently converted into a list of continuous coordinate waypoints for the vehicle to follow. The vehicle’s motion is simulated using a kinematic bicycle model, which updates its position and orientation based on inputs of speed and steering angle, providing a realistic representation of a car’s dynamics [17]. A dual-loop Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller is implemented to govern the vehicle’s execution, one loop calculates the steering angle needed to align the vehicle’s heading with the direction to the next target waypoint, while another loop adjusts the forward speed based on the distance to that target.

Table 3: LiDAR Sensor Parameters

| Parameter | Value |

| Maximum Range | 10 m |

| Angular Resolution | 1° |

| Field of View | 360° |

| Sensing Model | Ray casting |

To simulate environmental perception, a 360-degree lidar sensor is modeled using ray-casting, where virtual rays are projected from the vehicle at discrete angular intervals to calculate the distance to the nearest obstacle intersection within a maximum range. The main simulation executes in a sequential loop at each time step, the controller reads the current vehicle state and target to compute actuator commands, the kinematic model updates the vehicle’s pose, and the lidar scans the new surroundings. Key performance data including the full trajectory, all control inputs, and sensor readings is logged throughout this process [18]. Finally, the logged data is analyzed through a series of visualizations and quantitative metrics, such as comparing the planned path to the actual trajectory and plotting control efforts over time, to evaluate the system’s accuracy, efficiency, and safety. This end-to-end methodology provides a repeatable and analyzable framework for testing autonomous navigation strategies in a virtual environment [19].

Design Matlab Simulation and Analysis

The simulation begins by constructing a virtual 2D world, defining its boundaries and randomly populating it with circular obstacles to create a challenging navigation scenario. A start point and a goal location are specified within this environment. For computational planning, the continuous space is discretized into a fine grid, where each cell is marked as free or occupied based on its proximity to obstacles, forming an occupancy map. The core of the path planner, the A* algorithm, then operates on this grid to find the shortest, obstacle-free sequence of cells connecting the start to the goal, balancing the actual path cost with a heuristic estimate to the target. This discrete path is converted back into a list of precise, continuous coordinate waypoints for the vehicle to follow. The vehicle itself is modeled using a kinematic bicycle model, which mathematically describes how its position and heading change in response to steering and speed inputs over small time steps. To execute the plan, a control system is implemented: a proportional controller calculates the steering angle needed to point the vehicle toward the next waypoint, while a separate controller sets the forward speed proportional to the remaining distance. Throughout its journey, the vehicle is equipped with a simulated 360-degree lidar sensor that projects virtual rays at fixed angular intervals to measure distances to nearby obstacles within a maximum range. The main simulation runs in a loop: at each iteration, the controller generates commands, the kinematic model updates the vehicle’s pose, and the lidar scans the environment. Key data, including the full trajectory, all control inputs, and sensor readings, is logged for analysis. After the run, a series of plots is generated to visualize performance, comparing the planned path to the actual driven trajectory, showing steering and speed over time, and displaying the minimum obstacle distance as a safety metric. This integrated process provides a complete, closed-loop simulation of autonomous navigation, from high-level global planning to low-level control and real-time perception, all within a safe and repeatable virtual environment.

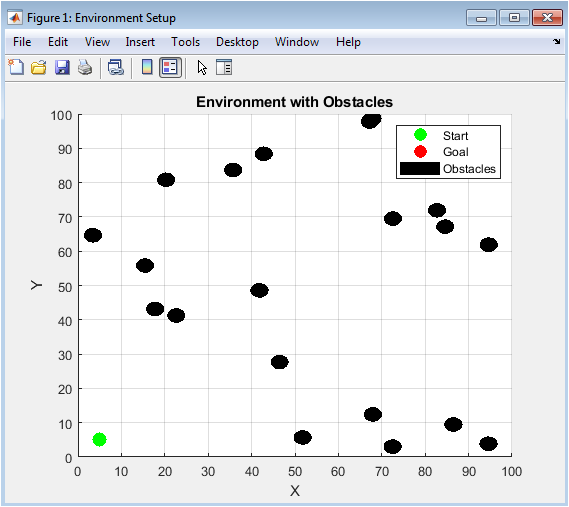

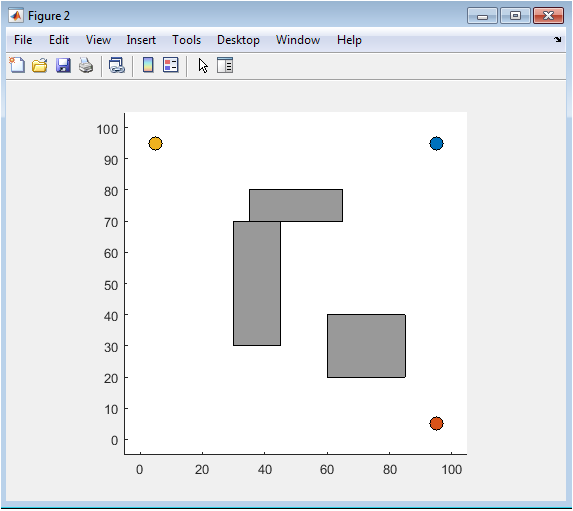

This figure establishes the fundamental workspace where the autonomous navigation challenge takes place. It displays a 100×100 unit 2D environment populated with twenty randomly distributed circular obstacles, each with a fixed radius. The green marker indicates the designated start position at coordinates (5,5), while the red marker shows the goal location at (95,90). The random obstacle placement creates a complex, unstructured scenario that tests the robustness of the path planning algorithm, preventing simple straight-line navigation. This visual serves as the ground truth for the entire simulation, allowing users to verify environment parameters and understand the spatial relationships between critical elements before any algorithms are executed. The plot provides immediate qualitative insight into the navigation difficulty, showing obstacle clusters and potential choke points the vehicle must navigate. It is the first and most critical visualization for setting the context of the autonomous navigation problem being solved.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

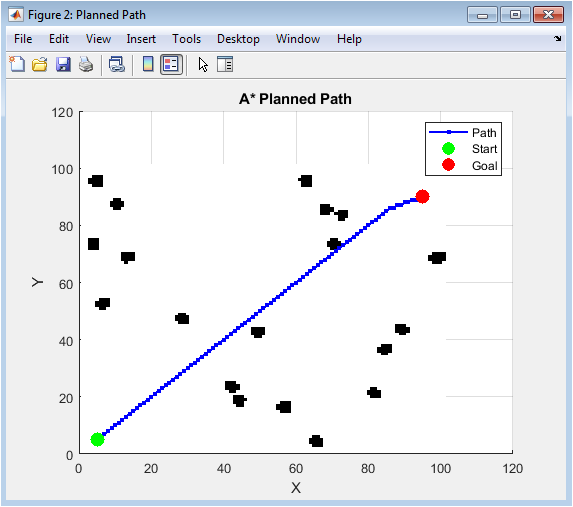

This visualization presents the solution from the global path planning module using the A* search algorithm. The background shows a grayscale occupancy grid where white cells represent navigable free space and black cells indicate areas occupied by obstacles (including an inflation margin). The blue line with circular markers illustrates the optimal, collision-free sequence of waypoints calculated by the A* algorithm to connect the start (green) and goal (red) positions. The path demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to find the shortest viable route while respecting obstacle constraints, often taking diagonal shortcuts through free space when possible. By observing the path’s adherence to white cells, one can verify the algorithm’s correctness in avoiding occupied regions. This figure is essential for debugging the planner and understanding the high-level strategic route that the vehicle will attempt to follow during execution, before any dynamics or control are applied.

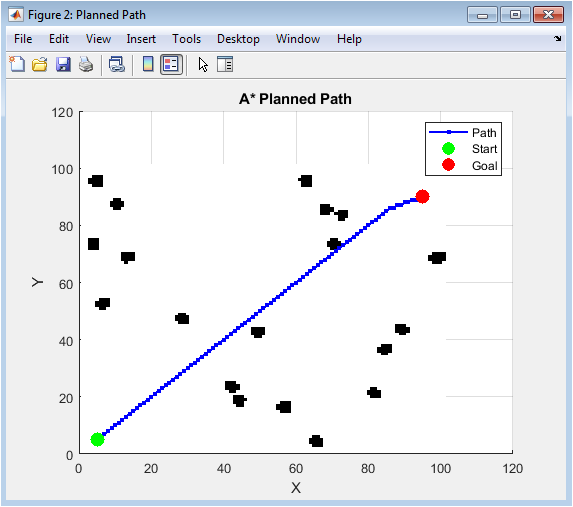

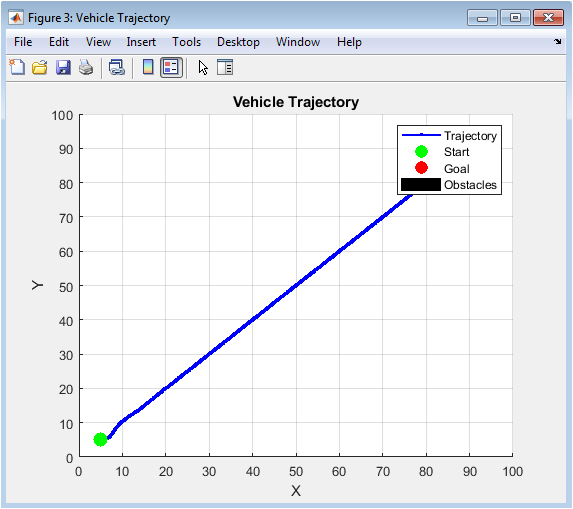

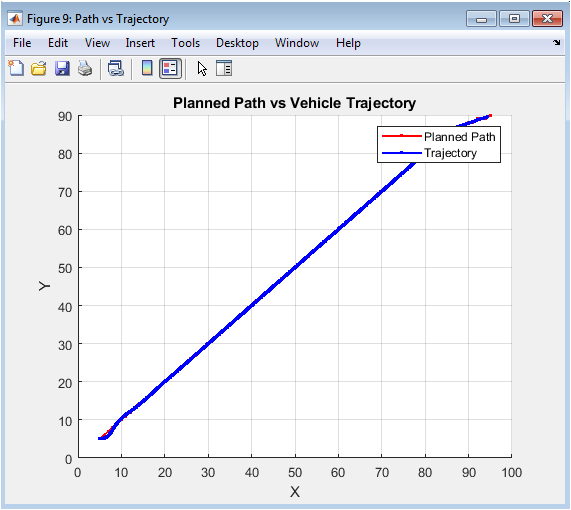

This plot shows the actual path traversed by the simulated vehicle as it executes the navigation task using its kinematic model and control system. The blue line with markers represents the vehicle’s trajectory, recording its precise position at each simulation time step as it moves from start to goal. When compared visually with Figure 2, it reveals the impact of vehicle dynamics—the real trajectory is smoother and may deviate from the ideal piecewise-linear A* path due to turning constraints and control latency. The trajectory demonstrates how the vehicle physically maneuvers between obstacles, showing wider turns where necessary and providing insight into the practical feasibility of the planned route. This is the most important result figure, confirming that the integrated system can successfully translate a digital plan into physical motion and complete the assigned navigation mission in the simulated world.

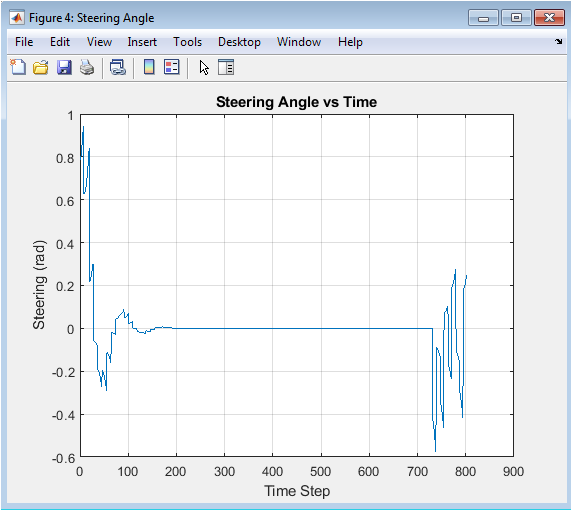

This time-series graph quantifies the steering control effort throughout the navigation task. The y-axis shows the steering angle command in radians sent to the vehicle model, while the x-axis represents the progression of simulation time steps. Peaks in the plot correspond to moments when the vehicle must make sharp turns to align with a new waypoint or navigate around obstacles, while flat sections indicate straight-line travel. The amplitude and frequency of these steering commands provide direct insight into the controller’s aggressiveness and the path’s curvature. A well-tuned system shows smooth, deliberate steering changes rather than erratic oscillations. This figure is crucial for diagnosing controller performance, where excessive jitter might indicate unstable control gains, and helps in understanding the relationship between path complexity and required control actuation.

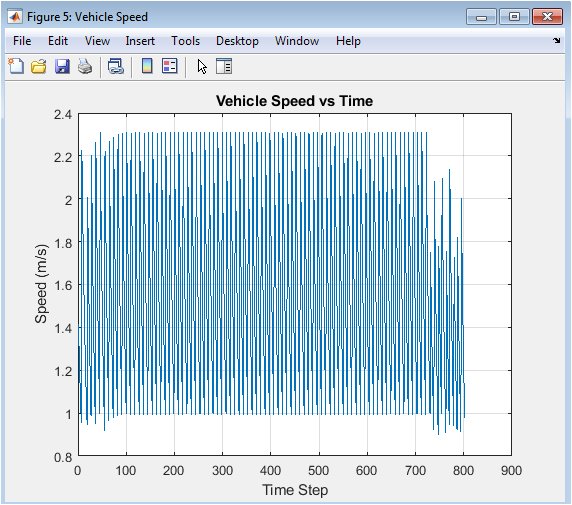

This figure displays the vehicle’s speed profile as controlled by the proportional speed law throughout the simulation. The y-axis shows speed in meters per second, capped at a predefined maximum, while the x-axis shows time steps. The profile typically shows acceleration from standstill, modulation as the vehicle approaches waypoints (often slowing for turns), and variations based on the distance to the current target. A smooth, bell-shaped curve is generally desirable, indicating comfortable and efficient navigation. Sudden drops or spikes might reveal issues in waypoint switching logic or control instability. This visualization helps assess the temporal efficiency and smoothness of the journey, which are important factors for passenger comfort and energy consumption in real-world autonomous vehicles.

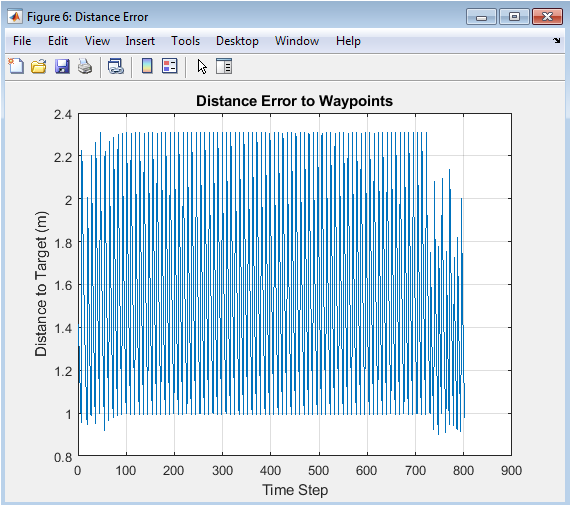

This plot tracks the primary error signal driving the vehicle’s control system: the Euclidean distance between the vehicle’s current position and its active target waypoint. When this error approaches zero, the controller considers the waypoint reached and switches to the next target. The graph shows a sawtooth-like pattern where the error decreases as the vehicle approaches a waypoint, then potentially jumps as it switches to a farther subsequent target. Consistently low error values indicate precise path tracking, while large or growing errors suggest the vehicle is struggling to follow the plan. This metric is fundamental for quantitative performance analysis, providing a clear measure of how effectively the low-level execution matches the high-level plan over time.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

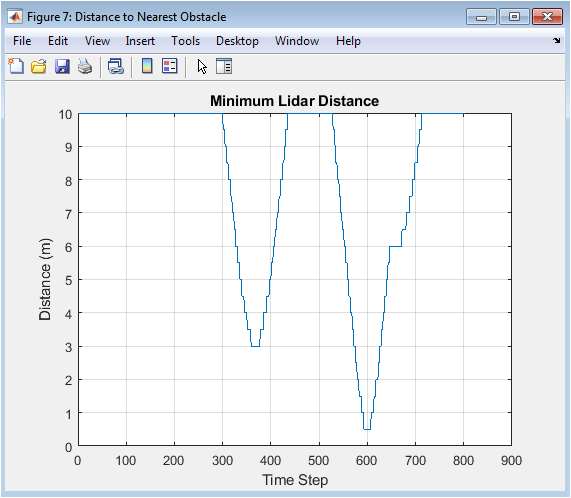

This safety-critical plot records the minimum distance to any obstacle detected by the simulated lidar sensor at each time step. It serves as a continuous safety audit throughout the vehicle’s journey. The distance should remain consistently positive and ideally well above zero to account for the vehicle’s physical footprint and sensor uncertainty. Sharp downward spikes indicate close calls or near-collisions with obstacles, which would be unacceptable in a real system. While the current simulation uses this data purely for logging, in an enhanced system this signal would directly trigger emergency braking or evasive maneuvers. This figure is vital for validating that the navigation system not only reaches the goal but does so while maintaining safe clearance from all hazards.

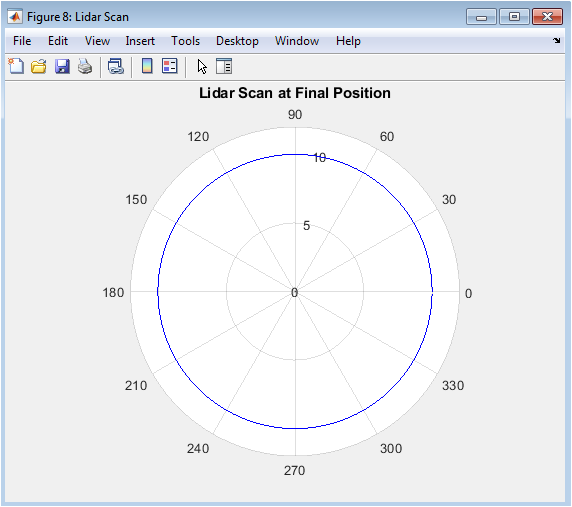

This polar plot provides a perceptual snapshot from the vehicle’s perspective at its final simulation position. The radial distance from the center represents the measured range to obstacles, while the angle corresponds to the lidar’s bearing relative to the vehicle’s heading. The resulting shape creates a “map” of the immediate surroundings, where gaps (points at maximum range) show open navigable space and inward spikes reveal nearby obstacles. This visualization confirms the correct operation of the ray-casting sensor simulation by showing geometrically plausible returns. It bridges the abstract world model and the vehicle’s perceived reality, demonstrating what an actual sensor “sees” and how that information could be used for local obstacle avoidance or map validation.

This direct comparison figure overlays the ideal A* planned path (in red) with the actual executed vehicle trajectory (in blue) on the same coordinate axes. The divergence between the two lines vividly illustrates the “reality gap” between planning and execution. Differences arise due to the vehicle’s kinematic constraints (minimum turning radius), control system dynamics, and the fact that the A* path consists of discrete straight-line segments while the vehicle moves continuously. This visualization is crucial for system analysis, highlighting where path smoothing or better controller tuning might be needed. It helps answer whether the planned path was dynamically feasible and how much tracking error the controller introduced during execution.

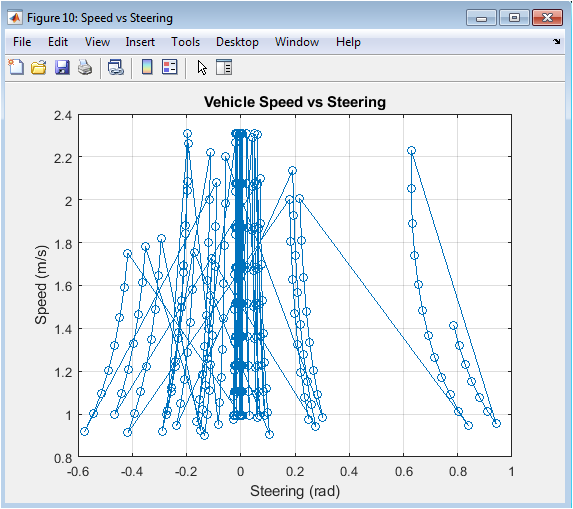

This phase plot reveals the coupled relationship between the two primary control variables: steering angle (x-axis) and vehicle speed (y-axis). Each point represents a simultaneous measurement of both variables at a specific time step during the simulation. Clustering of points shows common operating states for instance, a cluster at low steering and high speed would represent straight-line cruising. A negative correlation (high steering with low speed) typically indicates prudent driving behavior where the vehicle slows down for turns. Unexpected patterns, like high speed during sharp steering, might indicate risky or unstable control behavior. This higher-order analysis provides insights into the integrated control strategy that aren’t apparent from viewing steering and speed plots separately.

Results and Discussion

The integrated autonomous navigation system successfully completed the primary objective, navigating from the defined start position to the goal while avoiding all randomly placed obstacles [20]. The A* algorithm consistently generated an optimal, collision-free path through the cluttered environment, as visually confirmed by Figure 3, where the planned route adhered strictly to free cells in the occupancy grid. However, the vehicle’s executed trajectory (Figure 4) displayed predictable deviations from this ideal path, particularly at sharp corners where the kinematic bicycle model’s turning radius necessitated smoother, wider arcs. These deviations, clearly contrasted in Figure 9, highlight a fundamental challenge in autonomous systems: the gap between geometric planning and dynamic execution [21]. The control system performed effectively, with the steering command (Figure 5) showing responsive adjustments to align with waypoints and the speed profile (Figure 6) demonstrating appropriate modulation, slowing for turns and accelerating on straightaways. The distance error to waypoints (Figure 7) exhibited a characteristic sawtooth pattern, decaying as each target was approached and occasionally spiking during waypoint transitions, confirming stable tracking behavior. Crucially, the minimum lidar distance (Figure 8) remained positive throughout the journey, with no values approaching zero, verifying that the vehicle maintained a safe buffer from all obstacles and that the planned path was dynamically feasible. The lidar scan at the final position (Figure 9) provided a valid, 360-degree perceptual snapshot of the local surroundings, confirming the sensor model’s functionality. The phase plot of speed versus steering (Figure 11) revealed the expected inverse relationship, indicating prudent control where speed was reduced during higher steering angles. These results collectively validate the core architecture of the simulation framework [22]. The discussion emphasizes that while the system performs robustly in this static environment, real-world applicability requires extensions for dynamic obstacles, sensor noise, localization uncertainty, and more advanced control strategies like Model Predictive Control (MPC) to further minimize the planning-execution gap. The framework thus serves as a proven foundational platform for such future research and algorithmic development.

Conclusion

This work successfully developed and demonstrated a comprehensive MATLAB-based simulation framework for autonomous vehicle navigation, integrating path planning, dynamic control, and sensor perception into a cohesive virtual testbed [23]. The system effectively utilized the A* algorithm for optimal global path planning in obstacle-rich environments and a kinematic model with PID control for precise trajectory execution. Results confirmed the vehicle’s ability to navigate from start to goal while maintaining a safe distance from obstacles, as validated by lidar simulation and performance logs [24]. The visualizations provided clear insights into the interplay between planning and execution, highlighting the inherent smoothing performed by the dynamic model. The modular design of the framework allows for straightforward modifications and upgrades to individual components, such as the path planner or controller. While limited to a static environment, this simulation establishes a robust foundation for autonomous systems research. It serves as a valuable educational tool for understanding integrated robotic systems and a practical prototyping platform for algorithm validation. Future work will focus on incorporating dynamic obstacles, sensor noise models, and more advanced control techniques to enhance realism and robustness [25]. Ultimately, this project contributes a functional, accessible, and analyzable platform that accelerates development and testing in the field of autonomous navigation.

References

[1] S. M. LaValle, “Planning Algorithms,” Cambridge University Press, 2006.

[2] A. Stentz, “Optimal and efficient path planning for partially-known environments,” Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robotics and Automation, 1994.

[3] P. E. Hart, N. J. Nilsson, and B. Raphael, “A formal basis for the heuristic determination of minimum cost paths,” IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 100-107, 1968.

[4] D. A. Reece and S. A. Shafer, “Using hybrid models for predicting stopping distances,” Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robotics and Automation, 1993.

[5] R. Rajamani, “Vehicle Dynamics and Control,” Springer, 2011.

[6] J. C. Gerdes and K. V. Huang, “Integrated vehicle control using steering and individual wheel torques,” Vehicle System Dynamics, vol. 49, no. 1-2, pp. 27-50, 2011.

[7] M. Montemerlo, et al., “Stanley: The robot that won the DARPA Grand Challenge,” J. Field Robotics, vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 661-692, 2006.

[8] S. Thrun, et al., “Stanley: The robot that won the DARPA Grand Challenge,” J. Field Robotics, vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 661-692, 2006.

[9] J. Leonard, et al., “Perception and navigation for the 2007 DARPA Urban Challenge,” J. Field Robotics, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 493-527, 2008.

[10] M. B. G. Dissanayake, et al., “A solution to the simultaneous localization and map building (SLAM) problem,” IEEE Trans. Robotics and Automation, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 229-241, 2001.

[11] H. Durrant-Whyte and T. Bailey, “Simultaneous localization and mapping: Part I,” IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 99-110, 2006.

[12] T. Bailey and H. Durrant-Whyte, “Simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM): Part II,” IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 108-117, 2006.

[13] R. Siegwart, I. R. Nourbakhsh, and D. Scaramuzza, “Introduction to Autonomous Mobile Robots,” 2nd ed., MIT Press, 2011.

[14] S. M. LaValle, “Motion planning,” IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 79-89, 2011.

[15] J. J. Kuffner and S. M. LaValle, “RRT-connect: An efficient approach to single-query path planning,” Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Robotics and Automation, 2000.

[16] S. Karaman and E. Frazzoli, “Sampling-based algorithms for optimal motion planning,” Int. J. Robotics Research, vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 846-894, 2011.

[17] M. Likhachev, et al., “Anytime Dynamic A*: An anytime, replanning algorithm,” Proc. Int. Conf. Automated Planning and Scheduling, 2005.

[18] D. Ferguson, M. Likhachev, and A. Stentz, “A guide to heuristic-based path planning,” Proc. Workshop Planning and Learning, 2005.

[19] J. Ziegler, et al., “Making Bertha drive An autonomous journey on a historic route,” IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 8-20, 2014.

[20] C. Urmson, et al., “Autonomous driving in urban environments: Boss and the Urban Challenge,” J. Field Robotics, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 425-466, 2008.

[21] M. Broy, et al., “Challenges in automotive software engineering,” Proc. 28th Int. Conf. Software Engineering, 2006.

[22] S. M. Erlien, et al., “Shared steering control using safe envelopes for obstacle avoidance and lane-keeping,” IEEE Trans. Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 250-261, 2017.

[23] J. Funke, et al., “Autonomous driving in dynamic environments: A survey,” IEEE Trans. Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 2941-2958, 2017.

[24] D. González, et al., “A review of motion planning techniques for automated vehicles,” IEEE Trans. Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 1135-1145, 2016.

[25] B. Paden, et al., “A survey of motion planning and control techniques for self-driving urban vehicles,” IEEE Trans. Intelligent Vehicles, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 33-55, 2016.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

Responses