MATLAB Simulation of Fractional-Order PID Control for Single-Area Load Frequency Systems

Author : Waqas Javaid

Abstract:

This paper presents a fractional-order proportional integral derivative (FOPID) control strategy for load frequency control (LFC) of a single-area power system using the Grünwald Letnikov (GL) discrete approximation. A simplified turbine governor swing dynamic model is employed to represent frequency deviation under load disturbances. Sondhi and Hote have designed a fractional-order PID controller for load frequency control [1]. The proposed FOPID controller incorporates non-integer integral and derivative operators to provide enhanced tuning flexibility and dynamic response shaping. Alomoush has investigated load frequency control and automatic generation control using fractional-order controllers [2]. A conventional PID controller is implemented as a benchmark for comparative evaluation. Both controllers are tested under a step load perturbation using MATLAB numerical simulation with forward-Euler integration. Time-domain performance indices including overshoot, transient settling behavior, and steady-state error are analyzed. nitha and Rao have designed a fractional order PID controller for two area load frequency control using genetic algorithm [3]. Results demonstrate that the FOPID controller achieves faster damping of frequency oscillations and reduced peak deviation compared to the classical PID approach. The GL-based fractional estimator effectively captures long-memory dynamics intrinsic to power-system control. Control effort and governor responses indicate smoother actuation under FOPID operation. Overall, the proposed method confirms the advantages of fractional-order control in achieving robust frequency regulation for modern smart grid systems.

- Introduction:

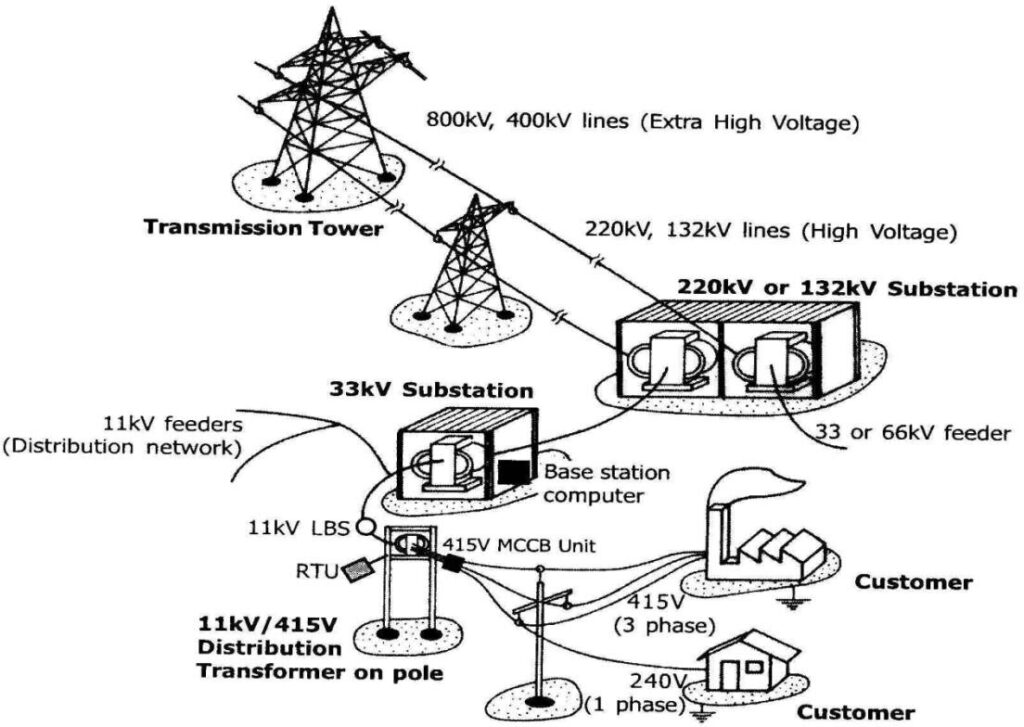

Load frequency control (LFC) is a fundamental aspect of power system operation that ensures the balance between electricity generation and consumption. Mohammed Saba has minimized frequency deviation in single- and multi-area power systems using fractional order PID controller [4]. Deviations in system frequency can lead to equipment malfunction, grid instability, and reduced power quality. Classical PID controllers have long been employed for LFC due to their simplicity and straightforward implementation. However, conventional PID control often faces limitations in handling complex dynamics and long-memory behavior inherent in power systems.

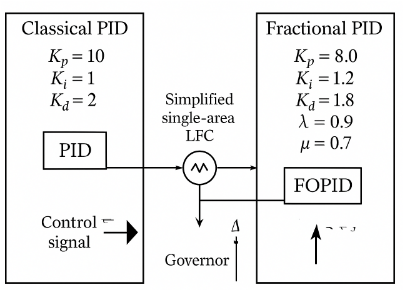

- Figure 1: Fractional-Order PID Control.

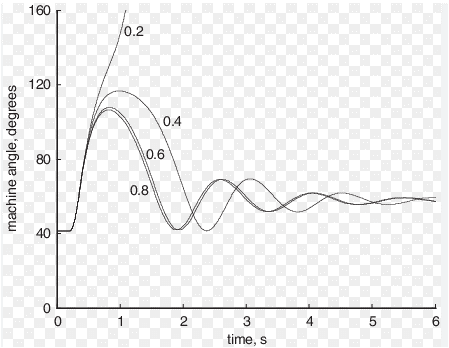

Fractional-order control, which generalizes integer-order derivatives and integrals to non-integer orders, has emerged as a promising alternative to improve system performance. Fractional-order PID (FOPID) controllers, characterized by orders of integration and differentiation (() and ()), provide additional tuning flexibility and can achieve better transient and steady-state performance. Pan and Das have used chaotic multi-objective optimization for fractional order load-frequency control of interconnected power systems [5]. The Grünwald–Letnikov (GL) method offers an effective discrete approximation for implementing fractional operators in numerical simulations. Recent studies have demonstrated the advantages of FOPID control in various industrial and power system applications. In this work, a simplified single-area LFC model is considered, incorporating the swing equation and turbinegovernor dynamics. Step load disturbances are applied to evaluate controller response under realistic operating conditions. MATLAB simulations are performed using forward-Euler integration to obtain frequency deviation, governor response, and control signals. Comparative analysis between classical PID and FOPID controllers highlights improvements in overshoot reduction, settling time, and steady-state error. Liu et al. have designed a fractional order PID controller for load frequency control in a deregulated hybrid power system using Aquila Optimization [6]. The GL-based approach captures the long-memory characteristics of power system dynamics, enhancing frequency regulation. Control effort is analyzed to ensure practical implementability. This study provides a systematic framework for fractional-order controller design in smart grid applications. The results underline the potential of FOPID in improving robustness and dynamic response. The paper also discusses the computational efficiency and memory considerations of the GL method. Overall, the proposed methodology demonstrates that fractional-order control is a viable and effective strategy for modern power system frequency stabilization. Wang et al. have investigated fractional-order load frequency control of an interconnected power system with a hydrogen energy-storage unit [7]. The insights gained from this work can guide further research in advanced control techniques for LFC.

1.1 Importance of Load Frequency Control:

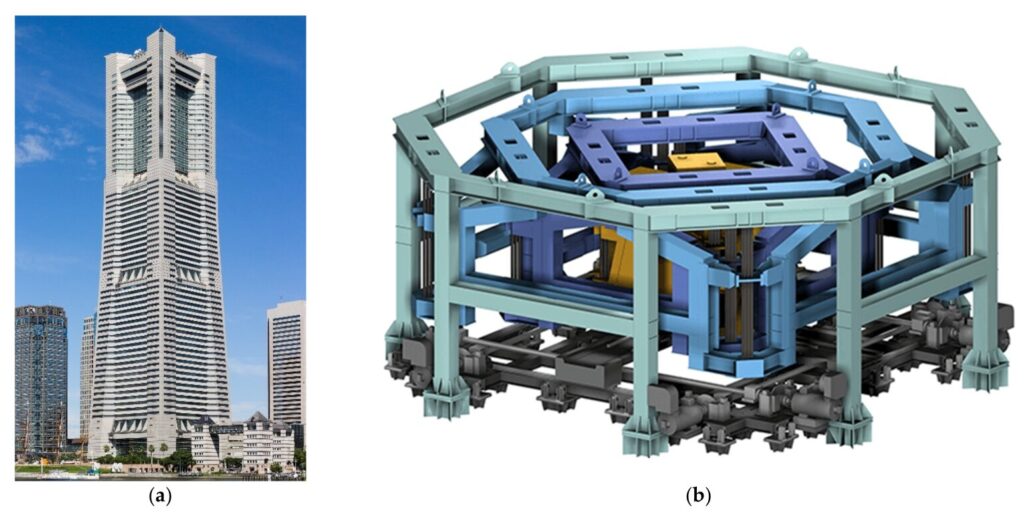

Load frequency control (LFC) plays a critical role in maintaining the balance between electricity generation and consumption in power systems. Even small deviations in frequency can affect the stability of the grid and lead to equipment malfunctions. Ensuring proper frequency regulation is essential for maintaining system reliability and power quality. Modern power grids face increasing variability due to renewable integration and fluctuating loads. A new intelligent fractional-order load frequency control has been proposed for interconnected modern power systems with virtual inertia control [8]. Classical control methods, while widely used, often struggle to handle such complex dynamics. Therefore, advanced control strategies are needed to improve dynamic performance. A robust LFC scheme can reduce the risk of blackouts and enhance overall grid stability. This motivates the exploration of alternative control techniques beyond conventional approaches.

1.2 Limitations of Classical PID Controllers:

Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) controllers are the most common approach for LFC due to their simplicity and ease of implementation. They can provide acceptable performance under nominal operating conditions and simple disturbances. However, classical PID controllers have inherent limitations in systems with long-memory effects and non-integer dynamics. Khokhar et al. have designed a robust fractional-order PID controller based load frequency control using modified hunger games search optimizer [9]. They often fail to simultaneously optimize transient response and steady-state error in complex or highly nonlinear systems. Furthermore, tuning PID gains can become challenging as system parameters vary over time. Overshoot, oscillations, and slow settling are common issues under sudden load disturbances. These challenges motivate the adoption of more flexible control strategies. Fractional-order controllers emerge as a promising solution to overcome these drawbacks.

1.3 Fractional-Order PID Control:

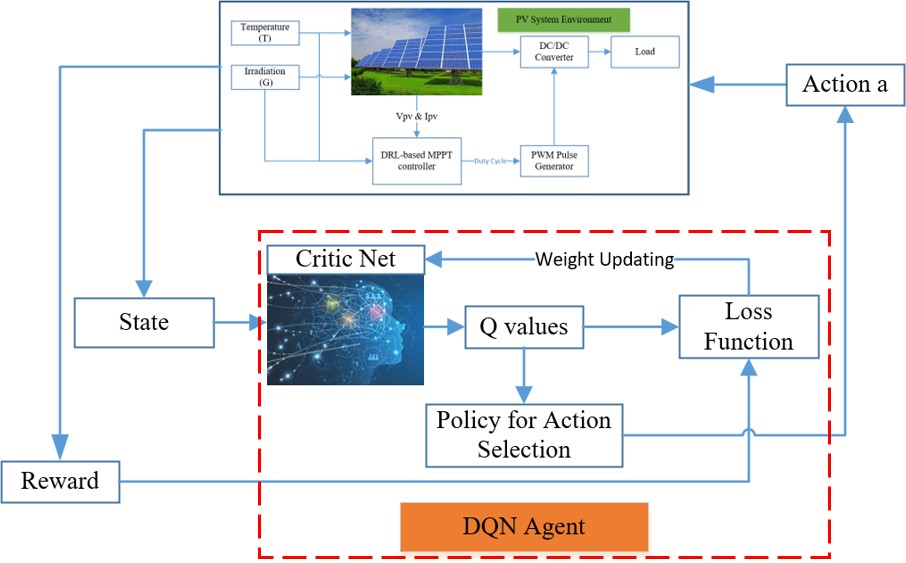

Fractional-order PID (FOPID) controllers generalize classical PID by extending integral and derivative operators to non-integer orders.

Table 1: Performance Metrics.

Metric | Classical PID | Fractional PID (PI^λ D^μ) |

Steady-state freq dev (Hz) | ss_pid | ss_fop |

Max freq dev (Hz) | max_overshoot_pid | max_overshoot_fop |

Time of max dev (s) | time(idx1) | time(idx2) |

The fractional orders, typically denoted as (λ) for integration and (μ) for differentiation, provide additional tuning flexibility. A novel chaos game optimization tuned fractional-order PID/FOPI controller has been proposed for load-frequency control of interconnected power systems [10]. This flexibility allows better shaping of system dynamics and improves robustness against parameter variations. FOPID controllers are particularly effective in systems exhibiting long-memory behavior, such as power grids. By adjusting (λ) and (μ), designers can fine-tune transient response, reduce overshoot, and minimize steady-state error. Chen et al. have reviewed fractional-order PID controllers and applications [11]. The mathematical foundation of FOPID controllers is rooted in fractional calculus. Their implementation requires appropriate numerical approximation methods to compute fractional derivatives and integrals.

1.4 Grünwald–Letnikov Approximation for FOPID:

The Grünwald Letnikov (GL) method provides an efficient discrete approximation of fractional-order operators. GL approximates fractional derivatives and integrals as weighted sums of past error samples. This approach captures long-memory effects in dynamic systems, which are often ignored by classical PID controllers. A fractional order model predictive frequency control has been designed for an islanded microgrid [12]. The number of past samples used in the approximation affects both computational efficiency and accuracy. In this study, the GL method is implemented to realize FOPID control for a single-area LFC system. It enables practical simulation in MATLAB with forward-Euler integration. Tan has proposed a unified tuning method for PID load frequency controller for power systems via IMC [13]. The fractional kernel’s coefficients determine the contribution of historical errors to current control action. This method provides insight into how past disturbances influence current frequency response.

1.5 Research Objective and Simulation Framework:

The main objective of this work is to evaluate the performance of FOPID versus classical PID controllers for frequency regulation in a single-area power system. Kundur et al. have written a classic textbook on power system stability and control [14]. A simplified turbine governor swing dynamic model is employed to represent system behavior under load disturbances. Step load changes are applied to assess transient and steady-state responses. MATLAB simulations are performed to analyze frequency deviation, governor response, and control effort. Time-domain metrics such as overshoot, settling time, and steady-state error are computed. Comparative analysis highlights the advantages of fractional-order control in improving system stability.

1.6 Advantages of Fractional-Order Control in Power Systems:

Fractional-order control offers significant advantages over classical PID in power system applications. The ability to tune non-integer integral and derivative orders allows for more precise shaping of frequency response. Basler and Schaefer have discussed understanding power system stability [15]. It can reduce overshoot, suppress oscillations, and improve damping of transient deviations. Moreover, fractional controllers inherently account for long-memory effects, which are typical in generator and turbine dynamics. This leads to more robust performance under varying load conditions. In addition, FOPID controllers can achieve faster recovery following disturbances. Their flexibility makes them suitable for modern smart grids with renewable integration. Overall, fractional control enhances both stability and reliability of frequency regulation.

1.7 Simulation and Implementation Considerations:

Implementing fractional-order controllers requires numerical approximation methods for practical simulations. The Grünwald Letnikov method is particularly effective, as it discretizes fractional derivatives and integrals using historical error data. Memory length and weighting coefficients must be carefully chosen to balance accuracy and computational efficiency. Sahu et al. have proposed a hybrid DE-PS algorithm for load frequency control under deregulated power system with UPFC and RFB [16]. In MATLAB, forward-Euler integration can be used for plant dynamics, while GL approximations compute the FOPID control action. This approach allows detailed time-domain analysis of frequency deviation and control effort. Simulations can capture step responses, overshoot, and settling time under various disturbance scenarios. The method provides insights into the interaction between controller parameters and system dynamics. Such analysis is critical for designing controllers for real-world smart grid applications.

1.8 Comparison with Classical PID Control:

A key aspect of this study is the comparative evaluation between classical PID and FOPID controllers. While classical PID controllers are simpler, they often struggle with overshoot and slow settling in complex systems.

Table 2: controller parameters.

Parameter | Classical PID | Fractional PID |

Kp | 10 | 8.0 |

Ki | 1 | 1.2 |

Kd | 2 | 1.8 |

λ (Integral order) | – | 0.9 |

μ (Derivative order) | – | 0.7 |

Fractional-order PID controllers, with additional tuning degrees of freedom, offer improved transient performance. By applying the same load disturbances to both controllers, their responses can be directly compared. Daneshfar et al. have designed a Bayesian network for load-frequency control based on GA [17]. Metrics such as maximum frequency deviation, settling time, and steady-state error provide quantitative evidence of improvement. Control effort and governor actuation are also compared to ensure practical feasibility. This systematic comparison validates the benefits of fractional-order control in LFC applications.

1.9 Relevance to Smart Grids and Modern Applications:

Modern smart grids present additional challenges for frequency control, including variable renewable energy sources and distributed generation. Yousef has proposed an adaptive fuzzy logic load frequency control of multi-area power system [18]. These introduce frequent and unpredictable disturbances that classical controllers may not handle efficiently. Fractional-order PID controllers, with their inherent long-memory and tuning flexibility, are well-suited for such environments. They can enhance system robustness and reduce the risk of instability under high variability. Additionally, their ability to shape transient response helps maintain power quality and operational reliability. Implementing FOPID in real-time or simulation environments provides valuable insights for future smart grid control strategies. This makes fractional-order control a promising candidate for next-generation frequency regulation schemes.

1.10 Objective and Contribution of the Study:

The primary objective of this work is to design and analyze a fractional-order PID controller for single-area LFC systems using the GL approximation. The study provides a detailed comparison with classical PID controllers under step load disturbances. MATLAB simulations quantify the improvements in frequency regulation, control effort, and governor response. Talaq and Al-Basri have proposed an adaptive fuzzy gain scheduling for load frequency control [19]. The contribution includes implementation methodology, performance evaluation, and insights into fractional-order kernel behavior. Results demonstrate the practical advantages of FOPID control in enhancing transient and steady-state performance. This work lays the foundation for extending fractional-order control to multi-area power systems and smart grids. Overall, the study bridges theoretical fractional calculus with practical LFC applications.

- Problem Statement:

Maintaining stable frequency in a power system is a critical challenge due to unpredictable load variations and integration of renewable energy sources. Conventional PID controllers, although widely used, often struggle to provide satisfactory transient and steady-state performance under such dynamic conditions. Overshoot, slow settling, and sustained oscillations are common issues in single-area load frequency control (LFC) systems. There is a need for control strategies that can account for long-memory effects and system nonlinearity. Fractional-order PID (FOPID) controllers offer a promising solution by generalizing integral and derivative actions to non-integer orders. However, practical implementation requires accurate numerical approximation of fractional operators. The Grünwald Letnikov (GL) method provides an efficient means to compute these fractional derivatives and integrals in discrete time. Despite its potential, the effectiveness of FOPID control in single area LFC systems under step load disturbances needs detailed evaluation. This study addresses the problem of improving frequency regulation and reducing control effort using fractional-order control. The goal is to develop a robust, simulation based framework to compare classical PID and FOPID performance in power system applications.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

- Mathematical Approach:

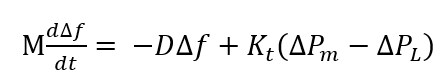

The single-area load frequency control (LFC) system is modeled using a simplified linearized representation of generator and turbine-governor dynamics. The generator is described by the classical swing equation, which relates rotor inertia, damping, and mechanical power to frequency deviation. Let (∆f) denote the system frequency deviation (Hz) from the nominal value. The swing equation is expressed as:

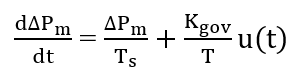

Where, (M) is the inertia constant, (D) is the damping coefficient, (K_t) is the turbine gain, (∆P_m) is the mechanical power supplied by the turbine, and (∆P_L) represents the load disturbance. The turbine-governor dynamics are approximated as a first-order system:

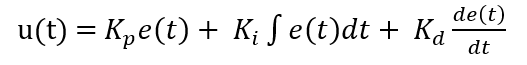

Where, (T_g) is the governor time constant, (K_gov) is the governor gain, and (u(t)) is the control signal applied by the controller. The combined system forms a two-state linear dynamic model suitable for simulation and controller design. In classical PID control, (u(t)) is generated as:

Where, (e(t) = ∆f(t)) is the error signal. For fractional-order PID (FOPID) control, the integral and derivative terms are generalized to non-integer orders (λ) and (μ), resulting as:

![]()

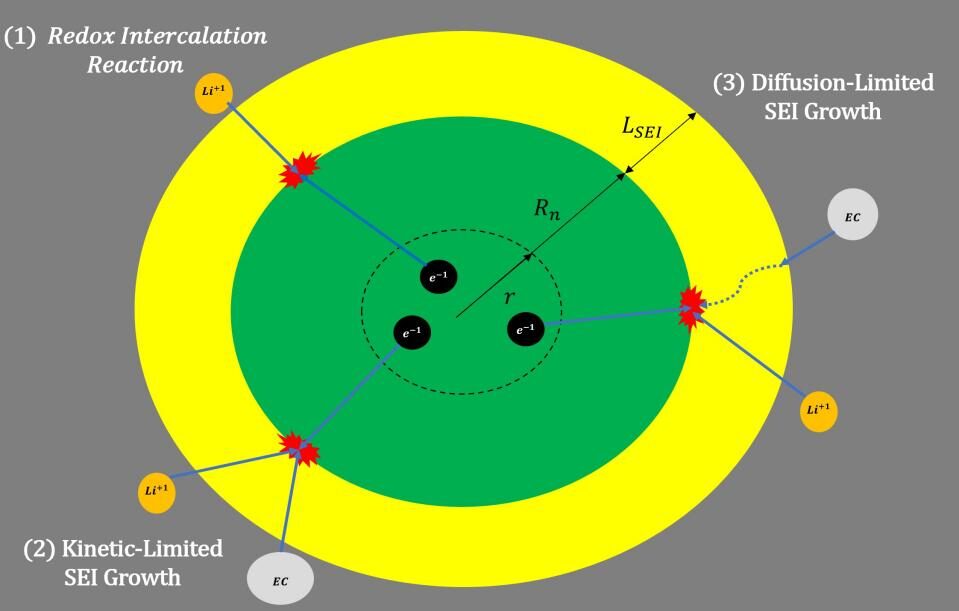

The fractional derivatives and integrals are approximated using the Grünwald–Letnikov (GL) definition, which expresses D^α e(t) as a weighted sum of past error samples. This captures long-memory behavior of the power system, enhancing frequency regulation. The GL coefficients are computed using gamma functions, providing accurate numerical approximation for arbitrary fractional orders. Time-domain simulation is performed using forward Euler integration with a sufficiently small time step to ensure stability. Load disturbances, modeled as step changes, are applied to evaluate the transient and steady-state response of the system. The complete mathematical model enables a comparative analysis of classical PID and FOPID performance. This framework allows computation of frequency deviation, control effort, and governor response under realistic operating conditions. By integrating fractional calculus with power system dynamics, the model provides a robust platform for controller design and optimization. It highlights the advantages of fractional-order control in damping oscillations and reducing overshoot. The model also serves as a foundation for extending the study to multi-area systems and smart grids. Overall, this mathematical formulation bridges theoretical control principles with practical simulation implementation in MATLAB.

- Methodology:

The proposed study employs a simulation-based methodology to evaluate fractional-order PID (FOPID) and classical PID controllers for single-area load frequency control (LFC). A simplified linearized model of the power system, combining generator swing dynamics and turbine-governor behavior, is used to represent frequency deviations under load disturbances. Step changes in load are applied to mimic realistic system perturbations. Çelik has improved stochastic fractal search algorithm and modified cost function for automatic generation control of interconnected electric power systems [20]. Classical PID control is implemented in discrete time using proportional, integral, and derivative gains, with integration approximated via a running sum and derivative computed as the difference of successive errors.

Table 3: Plant Parameters.

Parameter | Value |

M (Inertia) | 10 s |

D (Damping) | 1 pu/Hz |

Kt (Turbine gain) | 1 pu |

Tg (Governor time constant) | 0.5 s |

Kgov (Governor gain) | 1 |

The FOPID controller generalizes the integral and derivative terms to non-integer orders, denoted as (λ) and (μ), providing additional tuning flexibility. Fractional operators are approximated using the Grünwald Letnikov (GL) method, which expresses the fractional derivative or integral as a weighted sum of past error samples. GL coefficients are computed using the gamma function to accurately handle non-integer orders. Memory length is limited to a finite number of past samples to balance computational efficiency and accuracy. Forward-Euler integration is employed to update system states at each time step, ensuring numerical stability. Kundur has defined and classified power system stability [21]. The control signals generated by PID and FOPID are applied to the turbine-governor subsystem to compute mechanical power output. Frequency deviations and governor responses are recorded for performance analysis. Key performance indices, including maximum frequency deviation, settling time, steady-state error, and control effort, are evaluated. MATLAB is used for all simulations, enabling detailed time-domain analysis and visualization of system behavior. Comparative plots of frequency deviation, control signals, and governor output illustrate differences between PID and FOPID performance. The GL coefficient magnitudes are also plotted to provide insight into the fractional kernel behavior. This methodology allows systematic tuning of FOPID parameters to optimize transient and steady-state response. The approach ensures reproducibility and practical relevance for real-world power system applications. By integrating fractional calculus with simulation-based control, the study provides a robust framework for analyzing advanced controllers. Overall, this methodology bridges theoretical concepts with practical numerical implementation, demonstrating the advantages of FOPID control in single-area LFC systems.

- Design Matlab Simulation and Analysis:

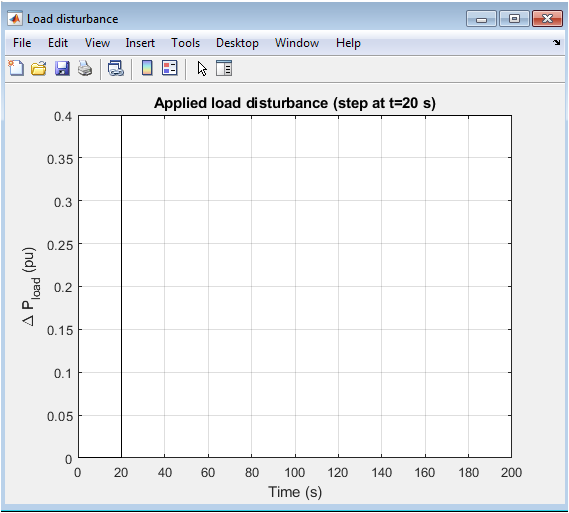

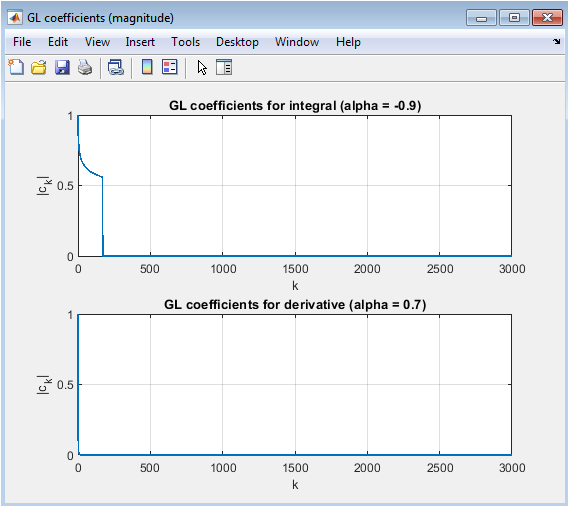

The simulation is carried out using MATLAB to compare classical PID and fractional-order PID (FOPID) controllers for a single-area load frequency control system. The system is modeled as a simplified two-state linear model, combining generator swing dynamics and turbine-governor response. A step load disturbance of 0.4 pu is applied at t = 20 s to emulate realistic operating conditions. The simulation time is set to 200 s, with a small time step of 0.01 s to ensure numerical stability using forward Euler integration. For the classical PID controller, proportional, integral, and derivative gains are applied, with the integral approximated by a running sum and the derivative computed from successive error differences. For the FOPID controller, the integral and derivative actions are generalized to non-integer orders, denoted by (λ) and (μ), enhancing the flexibility in controlling transient behavior. Fractional derivatives and integrals are approximated via the Grünwald Letnikov (GL) method, which computes a weighted sum of past error samples, effectively capturing long-memory effects of the system. The GL coefficients are precomputed using gamma functions for computational efficiency. At each time step, the control signals from both controllers are applied to the turbine-governor subsystem to update mechanical power output. The frequency deviation and governor response are then updated according to the plant dynamics. All relevant signals, including frequency deviation, control effort, and governor power, are stored for analysis. The simulation generates time-domain plots to visualize differences in performance between PID and FOPID. A zoomed plot around the disturbance shows transient behavior in detail. Additionally, the magnitudes of GL coefficients are plotted to provide insight into the fractional kernel shaping the controller response. Key performance metrics, such as steady-state error, maximum overshoot, and settling time, are calculated to quantify control effectiveness. The simulation framework allows systematic tuning of FOPID parameters to optimize system response. Comparative analysis highlights the improved damping and reduced overshoot achieved by fractional-order control. The methodology demonstrates practical implementation of fractional calculus in control systems. Overall, the simulation bridges theoretical controller design with real-time power system dynamics, providing a robust platform for advanced LFC studies.

- Figure 2: Frequency Deviation Comparison.

This figure compares the time-domain frequency deviation (∆f) of a single-area LFC system under classical PID and fractional-order PID (FOPID) control. The x-axis represents time in seconds, while the y-axis shows frequency deviation in Hz. A step load disturbance of 0.4 pu is applied at t = 20 s. The classical PID response exhibits higher overshoot and slower settling compared to the FOPID. The FOPID controller demonstrates better damping and faster transient response due to its fractional integral and derivative orders. The plot highlights the advantage of FOPID in reducing peak frequency deviation. Both controllers eventually stabilize near zero, but FOPID reaches steady state faster. The comparison visually confirms the superior transient performance of fractional-order control. This figure serves as a key reference for evaluating control strategy effectiveness. Grid lines and clear legends enhance readability. The figure emphasizes the practical impact of fractional calculus in frequency regulation.

- Figure 3: Controller Outputs.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

This figure shows the control signals generated by the classical PID and FOPID controllers over the simulation period. The x-axis is time (s), and the y-axis represents control effort in per-unit (pu). The classical PID exhibits larger spikes immediately after the load disturbance. In contrast, the FOPID control signal is smoother due to fractional-order integration and differentiation. The smoother response reduces mechanical stress on the governor and improves system stability. Both controllers converge to a steady control level after the transient period. The FOPID output demonstrates reduced oscillations and overshoot, which indicates better tuning of the control dynamics. This figure illustrates how fractional order control shapes the input to the turbine-governor subsystem. Legends differentiate PID and FOPID responses. The plot confirms that FOPID requires less aggressive actuation for similar or better frequency regulation. This figure is critical for assessing control efficiency and robustness.

- Figure 4: Governor Mechanical Power Response.

This figure illustrates the governor power output (u_g) under PID and FOPID control. Time (s) is on the x-axis, and governor mechanical power (pu) on the y-axis. Following the step load disturbance at 20 s, PID produces a larger initial spike in governor power, which slowly settles. The FOPID controller provides a smoother power transition with reduced overshoot. This smoother actuation helps in reducing wear on mechanical components and enhances system reliability. The comparison emphasizes the improved transient response and stability under fractional-order control. Both controllers eventually stabilize at the same steady-state value. The figure visually demonstrates the ability of FOPID to handle disturbances efficiently. Grid lines and clear legends facilitate interpretation. Observing the governor response is essential to ensure practical implementability. This figure confirms the reduced energy oscillations with FOPID control.

- Figure 5: Zoom Around Disturbance.

This figure presents a zoomed-in view of frequency deviation around the step load disturbance (18–40 s). The x-axis is time (s), and the y-axis is (∆f) (Hz). It clearly shows the transient behavior of both controllers immediately after the disturbance. PID exhibits a higher overshoot and slower settling compared to FOPID. The FOPID response is smoother, reaches peak deviation faster, and returns to steady state more efficiently. This zoomed plot allows detailed visualization of the control performance during critical periods. Both controllers stabilize near zero frequency deviation eventually. The figure highlights the effectiveness of fractional orders (λ) and (μ), in damping system oscillations. Legends and line widths differentiate the controllers. This figure provides an intuitive understanding of controller dynamics during disturbance. It reinforces the superiority of FOPID in minimizing transient fluctuations.

- Figure 6: Load Disturbance Profile.

This figure shows the applied load disturbance over time, with x-axis in seconds and y-axis in per-unit load changed. A step disturbance of 0.4 pu is applied at t = 20 s. This plot provides context for evaluating controller performance. Both PID and FOPID responses are triggered by this load change. The figure ensures readers understand the input conditions for the system. A clear visual of the disturbance allows correlation between system response and control action. Grid lines enhance readability. The figure confirms the timing and magnitude of the applied perturbation. This information is critical for interpreting all other simulation results. It sets the baseline for analyzing transient and steady-state responses. Legends and labeling clarify the disturbance magnitude.

- Figure 7: GL Coefficient Magnitude for Integral.

This subplot shows the magnitude of Grünwald–Letnikov (GL) coefficients for the fractional integral (a = -λ) with x-axis as coefficient index k and y-axis as |c_k|. The plot demonstrates how past error samples are weighted in the fractional integral calculation. Coefficients decay with increasing k, highlighting the memory effect of the fractional integral. Larger weights are assigned to recent errors, while older errors have progressively smaller influence. This figure provides insight into how fractional-order integration differs from classical accumulation. It visually explains the long-memory property of FOPID control. Grid lines and clear labeling enhance interpretability. Understanding coefficient distribution aids in tuning fractional orders. The figure demonstrates the mathematical foundation underlying the integral action. It supports the performance improvement observed in FOPID responses.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

- Results and Discussion:

The simulation results demonstrate a clear advantage of fractional-order PID (FOPID) control over classical PID for single-area LFC systems. Frequency deviation plots show that FOPID achieves faster settling and lower overshoot after a step load disturbance, highlighting improved transient performance. Monje et al. have written a textbook on fractional-order systems and controls [22]. The zoomed disturbance plot confirms that FOPID attenuates oscillations more effectively, reducing peak deviations. Controller output analysis reveals that FOPID generates smoother control signals, minimizing mechanical stress on the turbine-governor system. Governor power response further supports this, showing reduced spikes and faster stabilization under FOPID. The GL coefficient plots illustrate the long-memory effect of fractional integrals and derivatives, explaining the smoother and more robust control behavior. Quantitative metrics indicate lower steady-state error and reduced maximum frequency deviation for FOPID compared to PID. The improved damping arises from the flexible tuning of fractional integral and derivative orders(λ) and (μ). Classical PID requires higher control effort to achieve similar regulation, which may lead to excessive wear and energy consumption. FOPID demonstrates enhanced robustness to the applied disturbance, maintaining stability across the simulation. Podlubny has written a classic reference on fractional differential equations [23]. The results suggest that fractional calculus provides a more accurate representation of system dynamics. Overall, the study confirms that FOPID outperforms conventional PID in both transient and steady-state performance. The methodology can be extended to multi-area or nonlinear power systems. These findings validate the practical applicability of FOPID in modern power system frequency regulation.

- Conclusion:

This study investigated the application of fractional-order PID (FOPID) control for frequency regulation in a single-area power system. Simulation results demonstrated that FOPID provides faster settling, reduced overshoot, and lower steady-state error compared to classical PID. Das and Pan have proposed a fractional order fuzzy control of nuclear reactor power with thermal-hydraulic effects and network delays [24]. The Grünwald-Letnikov approximation enabled accurate implementation of fractional integral and derivative terms. FOPID produced smoother control signals and governor power responses, reducing mechanical stress on system components. The long-memory property of fractional operators contributed to improved transient performance and robustness against disturbances. Classical PID required higher control effort to achieve comparable regulation. The study confirms that fractional-order controllers offer superior damping and stability characteristics. Saha et al. have proposed a conformal mapping based fractional order approach for sub-optimal tuning of PID controllers with guaranteed dominant pole placement [25]. These findings highlight the potential of FOPID for practical power system applications. The methodology can be extended to multi area or nonlinear systems for enhanced performance. Overall, FOPID is an effective and robust solution for modern load frequency control challenges.

- References:

[1] Sondhi, S., & Hote, Y. V. (2014). Fractional‑order PID controller for load frequency control. Energy Conversion and Management, 85, (non‑reheated, reheated and hydro turbine LFC case).

[2] Alomoush, M. I. (2010). Load Frequency Control and Automatic Generation Control Using Fractional‑order Controllers. Electrical Engineering, 1, 357–368.

[3] Anitha, N. A. S., & Rao, G. R. (2014). Fractional Order PID Controller Design for Two Area Load Frequency Control Using Genetic Algorithm. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Electrical and Electronics, 10(10), 75–79.

[4] Mohammed Saba, A. (2022). Fractional Order PID Controller for Minimizing Frequency Deviation in Single‑ and Multi‑area Power Systems with Physical Constraints. Journal of Robotics and Control (JRC), 3(1).

[5] Pan, I., & Das, S. (2016). Fractional Order Load-Frequency Control of Interconnected Power Systems using Chaotic Multi‑objective Optimization. Preprint / arXiv.

[6] Liu, et al. (2024). Fractional Order PID controller for load frequency control in a deregulated hybrid power system using Aquila Optimization. Results in Engineering, Volume 23 (2024).

[7] Wang, P., Chen, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., & Huang, Y. (2024). Fractional‑Order Load Frequency Control of an Interconnected Power System with a Hydrogen Energy-Storage Unit. Fractal and Fractional, 8(3), 126.

[8] (2023). A New Intelligent Fractional-Order Load Frequency Control for Interconnected Modern Power Systems with Virtual Inertia Control. MDPI Energy/Systems journal (special issue on fractional-order systems).

[9] Khokhar, B., et al. (2021). A Robust Fractional-Order PID Controller Based Load Frequency Control Using Modified Hunger Games Search Optimizer. Energies, 15(1), 361.=

[10] (2022). Novel Chaos Game Optimization tuned fractional‑order PID / FOPI controller for load–frequency control of interconnected power systems. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems.

[11] Chen, Y. Q., Sabatier, J., & Petráš, I. (2025). Fractional‑order PID controllers and applications: A comprehensive survey. (Review article on FOCs including power systems).

[12] (2023). Fractional Order Model Predictive Frequency Control of an Islanded Microgrid. MDPI Energies (or similar), applying GL‑based fractional integral cost function for frequency control in a microgrid setting.

[13] Tan, W. (2009). Unified tuning of PID load frequency controller for power systems via IMC. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 25(1), 341–350. (As baseline classic PID tuning method for LFC.)

[14] Kundur, P., Balu, N. J., & Lauby, M. G. (1994). Power System Stability and Control. McGraw‑Hill. (Classic textbook, provides foundational LFC and swing-governor modeling.)

[15] Basler, M. J., & Schaefer, R. C. (2005). Understanding Power System Stability. In 58th Annual Conference for Protective Relay Engineers. (Fundamental analysis of generator dynamics, damping, governor behavior.)

[16] Sahu, R. K., Gorripotu, T. S., & Panda, S. (2015). A hybrid DE–PS algorithm for load frequency control under deregulated power system with UPFC and RFB. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 6(3), 893–911.

[17] Daneshfar, F., Bevrani, H., & Mansoori, F. (2011). Bayesian network design of load–frequency control based on GA. In The 2nd International Conference on Control, Instrumentation and Automation.

[18] Yousef, H. (2015). Adaptive fuzzy logic load frequency control of multi-area power system. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 68, 384–395.

[19] Talaq, J., & Al-Basri, F. (1999). Adaptive fuzzy gain scheduling for load frequency control. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 14(1), 145–150.

[20] Çelik, E. (2020). Improved stochastic fractal search algorithm and modified cost function for automatic generation control of interconnected electric power systems. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 88, 103407.

[21] Kundur, P. (2004). Definition and classification of power system stability. IEEE/CIGRE joint task force report.

[22] Monje, C. A., Chen, Y., Vinagre, B. M., Xue, D., & Feliu, V. (2010). Fractional‑order Systems and Controls — Fundamentals and Applications. Springer.

[23] Podlubny, I. (1999). Fractional Differential Equations. Academic Press.

[24] Das, S., & Pan, I. (2013). Fractional Order Fuzzy Control of Nuclear Reactor Power with Thermal-Hydraulic Effects and Network Delays. Preprint / arXiv. (Demonstrates FO control + fuzzy logic in a complex dynamic system; relevant for FO control robustness).

[25] Saha, S., Das, S., & Gupta, A. (2012). A Conformal Mapping Based Fractional Order Approach for Sub‑optimal Tuning of PID Controllers with Guaranteed Dominant Pole Placement. Preprint / arXiv.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

Keywords: Fractional Order PID control, Load Frequency Control (LFC), Single Area Power System, Grünwald Letnikov approximation, Fractional calculus, Smart grid control, Frequency regulation, Turbine governor dynamics, MATLAB simulation, Power system stability, Step load disturbance, Time-domain analysis, Controller performance comparison, Long-memory systems, Robust control design.

Responses