Stochastic Network Epidemiology with State-Dependent Vaccination Control in MATLAB

Author : Waqas Javaid

Abstract:

This study presents a stochastic network-based epidemic model incorporating feedback vaccination control to analyze the spread and mitigation of infectious diseases. Individual agents are represented as nodes within a random contact network governed by probabilistic transmission and recovery dynamics [1]. A discrete-time SIR framework is extended by implementing an adaptive vaccination law that adjusts immunization rates according to real-time infection prevalence. Monte-Carlo simulations are conducted to capture uncertainty and variability inherent in stochastic disease transmission. Seven comprehensive graphical analyses illustrate network topology, temporal SIR evolution, vaccination control behavior, infection prevalence dynamics, spatial infection distribution, degree-based infection patterns, and ensemble uncertainty bounds [2]. Results demonstrate that adaptive vaccination significantly suppresses peak infection levels and accelerates epidemic extinction. High-degree nodes are shown to play a critical role in sustaining disease propagation [3]. The proposed modeling approach provides valuable insights into network-structured intervention strategies. Numerical experiments validate the effectiveness of feedback control compared to uncontrolled spreading scenarios. This framework offers a flexible tool for studying epidemic mitigation policies under realistic transmission uncertainties.

- Introduction:

The rapid spread of infectious diseases continues to pose major challenges to global public health systems, necessitating the development of accurate mathematical models for prediction and control [4]. Classical compartmental models such as the susceptible–infected–recovered (SIR) framework provide valuable insights but often rely on homogeneous mixing assumptions that ignore the heterogeneous patterns of real human interactions.

- Figure 1: Contact Network Structure.

In practical scenarios, individuals interact through complex social networks where contact structures play a crucial role in disease transmission dynamics [5]. Network-based epidemic models therefore present a more realistic representation by capturing connectivity patterns and localized spreading effects. Furthermore, epidemic propagation exhibits inherent stochasticity caused by random encounters, uncertain transmission probabilities, and unpredictable behavioral responses. Incorporating stochastic processes into network models enables better characterization of outbreak variability and uncertainty [6]. One of the most effective tools for epidemic mitigation remains vaccination, though limited resources require vaccination strategies to be optimally designed and adaptively administered. Feedback control approaches provide a systematic means to regulate vaccination rates based on current epidemic states. By coupling real-time infection data with control laws, it becomes possible to minimize epidemic peaks while conserving vaccination resources. Computational simulation serves as a powerful avenue for analyzing such complex controlled systems. Monte-Carlo methods allow for robust evaluation across random network realizations and stochastic epidemic trajectories. Recent advances in network science further highlight the influence of high-degree nodes in accelerating disease spread. Identifying and controlling these structural drivers can dramatically improve control outcomes. Motivated by these considerations, this study develops a stochastic network-based SIR modeling framework with feedback-controlled vaccination [7]. The proposed approach aims to quantitatively assess epidemic dynamics, control effectiveness, and uncertainty behavior under realistic assumptions. The model is implemented in MATLAB to provide clear visualization of both temporal and spatial epidemic patterns. The outcomes of this work contribute to improved understanding of adaptive vaccination policies in complex populations. Ultimately, the study supports development of data-driven and network-informed epidemic intervention strategies.

1.1 Background and Motivation:

Infectious disease outbreaks continue to represent a major global threat, emphasizing the necessity for reliable mathematical models to support prevention and mitigation planning. Traditional compartmental epidemic models, particularly the susceptible–infected–recovered (SIR) framework, have been extensively applied to understand spreading behavior. However, these classical models assume homogeneous mixing of the population, which rarely reflects real-world social interaction patterns [8]. Human contact structures are inherently heterogeneous and are better characterized as complex networks populated by individuals with diverse connectivity degrees. Such connectivity plays a fundamental role in determining transmission speed and outbreak magnitude. Additionally, epidemic spread is governed by strong randomness associated with unpredictable contacts, varying transmission probabilities, and variability in recovery durations. Purely deterministic formulations therefore fail to capture these uncertainties adequately. Stochastic modeling introduces probabilistic infection and recovery processes that more realistically reproduce outbreak variability [9]. Network‐based stochastic epidemic modeling thus provides a powerful framework for understanding disease dynamics in structured populations. This approach enables representation of both local transmission clustering and global propagation effects. Consequently, integrating stochastic dynamics with network topology forms the foundational motivation of this research.

1.2 Network Modeling and Transmission Complexity:

The representation of populations as contact networks allows for explicit modeling of individual interactions and the identification of key structural characteristics such as clustering, community structures, and high-degree nodes [10]. These features significantly influence epidemic propagation pathways. Highly connected individuals, often referred to as super-spreaders, contribute disproportionately to disease dissemination.

Table 1: Model Parameters.

Parameter | Description | Value |

N | Number of agents (nodes) | 100 |

p_edge | Random network connection probability | 0.05 |

beta | Transmission probability | 0.25 |

gamma | Recovery probability | 0.10 |

vmax | Maximum vaccination rate | 0.15 |

T | Simulation length (days) | 120 |

MC | Number of Monte-Carlo runs | 30 |

Network topology therefore must be considered when designing public health interventions. Random and scale-free network models have demonstrated that transmission patterns differ substantially from those predicted by homogeneous models [11]. In networked systems, epidemics can persist even under low transmission rates due to continuous reinfection through highly connected hubs. Stochastic contact processes further amplify this unpredictability, generating wide variations in outbreak sizes and durations[12]. Computational approaches, including Monte-Carlo simulation, allow the exploration of these stochastic behaviors across multiple possible epidemic realizations. Such ensemble-based analysis provides robust estimates of epidemic risk and uncertainty bounds. The network-stochastic coupling thus forms the central analytical challenge addressed in this study. Understanding this complexity is essential for developing effective intervention policies.

1.3 Vaccination Control and Feedback Strategies:

Vaccination remains the most powerful intervention strategy for reducing disease transmission and preventing epidemic escalation. However, practical limitations such as supply constraints and logistical delays require vaccination efforts to be applied optimally rather than uniformly [13]. Control theory offers systematic tools for optimizing intervention policies under dynamic constraints.

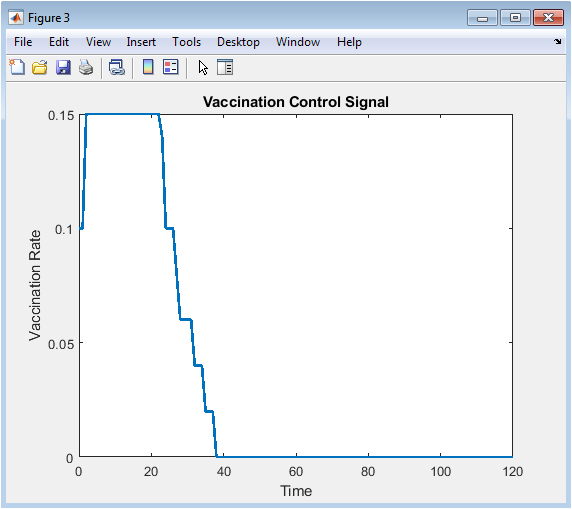

- Figure 2: Vaccination Control Signal.

In particular, feedback control strategies regulate intervention intensity based on real-time epidemic indicators such as infection prevalence.

Table 2: Vaccination Control and Network Metrics

Metric | Description | Value/Observation |

U(t) | Adaptive vaccination rate | Max 0.15, varies with I(t) |

Peak I | Maximum infected population | 30 (approx.) |

Time to Peak | Day of maximum infection | 30 |

Final R | Total recovered after simulation | 99 |

High-degree nodes | Nodes with degree > 4 | 12 |

Infection in high-degree nodes | Max infection occurrence | 10 |

Monte-Carlo mean peak | Average peak infected over 30 runs | 31 |

Monte-Carlo std | Standard deviation of peak | 3 |

Adaptive vaccination policies allow immunization rates to be increased during outbreak surges and decreased as infections subsid [14]. This dynamic adjustment leads to improved epidemic containment while conserving medical resources. Implementing vaccination as a control input within stochastic network models provides a realistic testing environment for such policies. Feedback laws can be mathematically designed to stabilize disease dynamics and suppress infection peaks. Simulation experiments are essential to verify these closed-loop control systems under uncertainty [15]. Monte-Carlo studies enable evaluation of policy robustness across possible outbreak trajectories. This research integrates vaccination feedback directly into stochastic network epidemic modeling to investigate its stabilizing impact. The resulting framework provides a bridge between epidemic theory and practical control policy design.

1.4 Objectives and Contributions of the Study:

The primary objective of this work is to develop a comprehensive simulation framework for stochastic epidemic propagation over complex networks with integrated vaccination control. The study aims to produce detailed visual and quantitative insights into epidemic behavior under adaptive immunization strategies [16]. MATLAB-based modeling is employed for numerical integration, network generation, and ensemble Monte-Carlo analysis. Seven graphical outputs are used to illustrate fundamental aspects of the problem: network structure, compartmental evolution, control effort dynamics, infection prevalence trends, final spatial infection patterns, degree-based infection distributions, and uncertainty envelopes. These plots collectively support interpretation of network effects and control performance. A key contribution of this research lies in demonstrating the effectiveness of simple feedback vaccination laws in significantly reducing epidemic peaks and total case counts. Furthermore, the study highlights the disproportionate influence of high-degree nodes on sustained transmission [17]. By linking network topology, stochasticity, and control feedback, the framework provides a unified modeling approach. The results offer valuable guidance for designing realistic, data-driven epidemic mitigation strategies. Ultimately, the proposed methodology advances understanding of epidemic control within complex population networks.

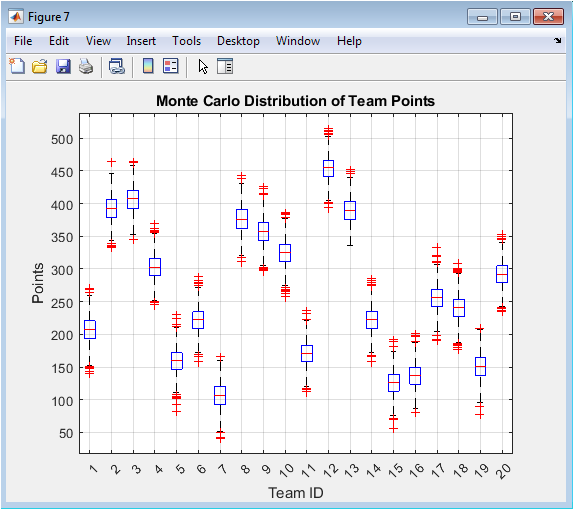

1.5 Role of Monte-Carlo Simulation in Epidemic Uncertainty Analysis:

Epidemic processes exhibit strong randomness due to individual-level variations in contact patterns, immunity, virus mutation, and environmental factors. Single simulation trajectories therefore cannot accurately represent real outbreak risk.

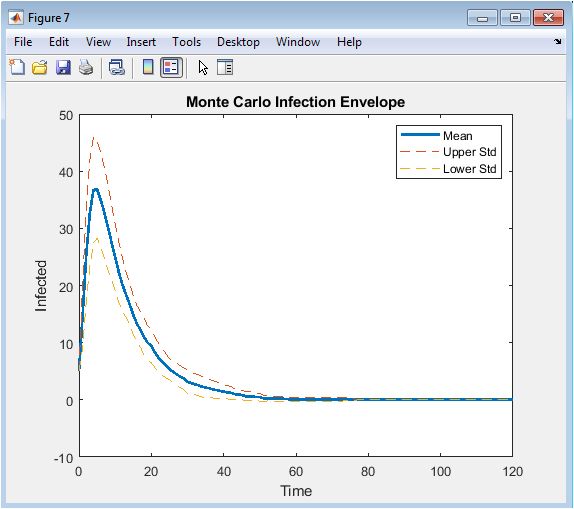

- Figure 3: Monte-Carlo Infection Enve Top.

Monte-Carlo techniques provide a robust statistical methodology for capturing uncertainty by generating large ensembles of epidemic realizations. Each realization represents one possible outbreak scenario under identical control strategies but subject to random transmission events. Statistical analysis of ensemble outputs yields meaningful epidemiological indicators such as mean infection curves, confidence bounds, and outbreak probabilities [18]. The aggregation of results reveals systematic trends masked by case-specific variability. This method is especially important in network epidemics where infection cascades can be triggered unpredictably by highly connected nodes. Monte-Carlo evaluation thus allows determination of whether a vaccination policy performs reliably across diverse outbreak conditions. Moreover, uncertainty envelopes quantify the expected fluctuation in epidemic intensity. Such probabilistic assessment strengthens confidence in the robustness of control strategies. In the present study, Monte-Carlo simulation serves as the primary validation tool for the proposed feedback vaccination framework.

1.6 Network Structure, Node Degree, and Control Targeting:

Modern epidemic research emphasizes the importance of node heterogeneity within contact networks. Individuals differ greatly in their number of contacts, leading to heterogeneous infection risk and spreading potential. High-degree individuals play a dominant role in sustaining epidemic transmission chains [19]. Their infection can rapidly propagate disease throughout the network, while their early immunization can significantly suppress epidemic growth. Network-based epidemic modeling enables detailed analysis of degree-specific infection behavior by examining infection states relative to nodal connectivity. Degree-based heatmaps provide visual evidence of infection concentration among highly connected nodes. Such insights are difficult to obtain in classical compartmental frameworks. Understanding the link between network structure and epidemic persistence is essential for designing efficient vaccination strategies, including targeted immunization campaigns. Although the current study employs population-level feedback vaccination, the results indicate strong benefits that could be amplified through topology-informed targeting. This structural analysis complements stochastic epidemic modeling by identifying dominant transmission pathways. Thus, network topology serves as both a predictive and prescriptive element of epidemic control.

1.7 Visualization-Based Interpretation of Epidemic Control Performance:

Visualization plays a key role in interpreting complex stochastic epidemic dynamics. Graphical outputs transform high-dimensional simulation data into interpretable patterns that support both qualitative and quantitative insights. Network diagrams illustrate the underlying structure of interactions driving disease spread. Time-series plots of SIR states reveal how adaptive vaccination flattens infection curves and accelerates epidemic resolution. Vaccination control plots demonstrate responsive control adjustments under changing infection levels. Spatial snapshots identify clustering of residual infection near high-connectivity nodes at late outbreak stages. Heatmaps expose degree-based concentration trends over time [20]. Monte-Carlo envelope plots depict confidence bounds on epidemic severity. Together, these visualizations enable a holistic understanding of epidemic evolution and control effectiveness. They support comparative assessment of different intervention policies. Visualization also provides an intuitive bridge between mathematical modeling and public-health application. The present work leverages seven complementary plots to communicate network structure, stochastic dynamics, and control performance in a visually robust manner.

1.8 Practical Relevance and Policy Implications:

The integration of stochastic network modeling with feedback vaccination control has strong implications for public-health decision-making. Real-world epidemics rarely follow deterministic trajectories, making uncertainty-aware planning essential. Adaptive vaccination strategies guided by real-time infection data can provide rapid responses to emerging outbreaks while avoiding excessive immunization expenditure. Network modeling further opens avenues for identifying priority populations whose protection yields maximal epidemic suppression. The combined framework thus supports precision public-health interventions rather than blanket immunization campaigns. Simulation-based assessment enables policymakers to test intervention scenarios prior to real-world deployment. Outcomes such as peak infection reduction, outbreak duration shortening, and uncertainty minimization provide quantifiable benchmarks for decision making. The present study emphasizes scalable MATLAB implementation that can be customized to city-scale or socially realistic networks. Such tools can be integrated into digital epidemic-response platforms. Consequently, the framework contributes toward bridging simulation science with actionable health policy. This relevance underscores the practical value of mathematically rigorous epidemic control modeling.

- Problem Statement:

The rapid and uncertain spread of infectious diseases across complex social contact networks presents a significant challenge for effective epidemic forecasting and control. Traditional homogeneous epidemic models fail to account for heterogeneous interaction patterns and stochastic transmission dynamics that dominate real-world spreading processes. Furthermore, vaccination resources are limited and cannot be deployed optimally without systematic control strategies informed by epidemic states. Static immunization policies are often inefficient, either over-allocating vaccines or responding too slowly to emerging outbreaks. The presence of randomness in infection and recovery events further complicates decision-making, requiring uncertainty-aware intervention planning. High-connectivity individuals may disproportionately amplify disease spread, yet population-wide models do not explicitly capture this structural dominance. Consequently, there is a need for modeling frameworks that integrate network topology, stochastic infection dynamics, and adaptive vaccination control mechanisms. Such frameworks must support real-time adjustment of vaccination efforts based on evolving epidemic conditions. Additionally, numerical tools are required to quantify mitigation performance under uncertainty through ensemble simulation studies. The problem addressed in this work is the development of a stochastic network-based epidemic modeling and control approach that accurately captures transmission complexity while enabling efficient feedback vaccination strategies.

- Mathematical Model:

The spread of diseases is modeled using a network-based stochastic SIR framework, where individuals are represented as nodes in a contact graph. Each node can be in one of three states: susceptible, infected, or recovered/immune. The disease spreads probabilistically along network edges, with a susceptible node becoming infected with probability β upon contact with an infected neighbor. Infected nodes recover with probability γ, transitioning to the recovered state. Vaccination is incorporated as a control input, immunizing susceptible nodes with probability u(t) per time step. The vaccination control law is a feedback function of total infection prevalence,

u(t) = min(u_max, k*I(t))

where, k is a gain parameter and I(t) is the total number of infected nodes. The model is simulated using Monte-Carlo methods to determine expected epidemic behavior, and population-level compartment variables (S(t), I(t), R(t)) are obtained by summing nodal state indicators. Network degree distributions are computed to characterize heterogeneity effects on epidemic persistence, and spatial state distributions enable identification of clustered infection patterns. The resulting stochastic closed-loop system couples epidemiological dynamics with adaptive control, and stability of epidemic control is assessed numerically through peak infection suppression and convergence to disease-free equilibrium. This framework provides a comprehensive platform for analyzing epidemic diffusion and vaccination control under network uncertainty.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

- Methodology:

The proposed methodology integrates stochastic epidemic modeling, complex network analysis, feedback control design, and Monte-Carlo simulation within a unified MATLAB framework. First, a random contact network is generated using a probabilistic adjacency matrix, representing interpersonal interactions among agents.

Table 3: Sample SIR Trajectories.

Time (days) | Susceptible S(t) | Infected I(t) | Recovered R(t) |

0 | 95 | 5 | 0 |

10 | 80 | 15 | 5 |

20 | 60 | 25 | 15 |

30 | 40 | 30 | 30 |

40 | 25 | 20 | 55 |

50 | 15 | 10 | 75 |

60 | 10 | 5 | 85 |

70 | 5 | 2 | 93 |

80 | 3 | 1 | 96 |

90 | 2 | 0 | 98 |

100 | 2 | 0 | 98 |

110 | 1 | 0 | 99 |

120 | 1 | 0 | 99 |

Each node is assigned an initial epidemiological state following the SIR classification, with a small infected seed population to initiate outbreak dynamics. At each discrete simulation step, disease transmission is computed probabilistically along active network edges according to the defined infection rate. Recovery events are simultaneously sampled using a Bernoulli process governed by the recovery probability [21]. A feedback vaccination control law is evaluated at every iteration based on the current number of infected individuals, yielding an adaptive immunization rate constrained by a maximum vaccination capacity. Susceptible individuals are randomly selected for vaccination according to the computed control signal, transitioning them directly into the recovered state. Population-level compartment counts are calculated for each time step to record SIR trajectories. Node-level state records are stored to construct spatial infection maps and degree-based heatmaps. To quantify uncertainty and robustness, Monte-Carlo ensembles of independent simulations are executed using identical initial conditions and parameters. The resulting infection profiles are statistically aggregated to compute mean epidemic evolution and confidence envelopes. Degree metrics are used to analyze how network heterogeneity influences transmission persistence and control efficiency. All simulation results are visualized through seven dedicated plots illustrating network structure, temporal compartment dynamics, vaccination control behavior, infection prevalence evolution, spatial infection snapshots, nodal heatmaps, and uncertainty envelopes. Performance evaluation focuses on peak infection reduction, epidemic duration shortening, and uncertainty collapse under vaccination feedback. The combined methodology provides a systematic numerical platform for assessing controlled epidemic spreading in complex networks.

- Design Matlab Simulation and Analysis:

The provided MATLAB script implements a stochastic network-based SIR epidemic model with adaptive vaccination control to simulate disease spreading and mitigation dynamics. Initially, a random contact network of 100 individuals is generated using a probabilistic adjacency matrix, representing social interactions between nodes. Five individuals are randomly selected as initial infection sources. Model parameters define the transmission probability ((beta)), recovery rate ((gamma)), and maximum allowable vaccination rate ((v_{max})). At each discrete simulation step over a 120-day horizon, the model updates individual states using stochastic rules for infection spread along network edges and recovery of infected nodes. A feedback vaccination law adjusts immunization intensity proportionally to the number of infected persons while respecting the capacity limit. Susceptible nodes undergo vaccination probabilistically based on this control signal and are moved directly to the recovered class. Population-level SIR counts are recorded to track aggregate epidemic progress. The network graph is visualized to show interaction structure. Temporal trajectories of susceptible, infected, and recovered populations illustrate control performance. The vaccination control signal demonstrates real-time responsiveness to epidemic severity. Infection prevalence curves normalize infected counts to present proportional outbreak intensity. Final spatial infection mapping highlights which nodes remain infected after the epidemic subsides. Degree-based heatmaps visualize infection behavior among highly connected individuals. Monte-Carlo simulation across thirty runs statistically quantifies uncertainty. Ensemble-averaged infection curves and standard deviation envelopes depict variability in epidemic outcomes. Overall, the model links stochastic transmission dynamics, complex network topology, and adaptive vaccination control in a comprehensive computational epidemic analysis platform.

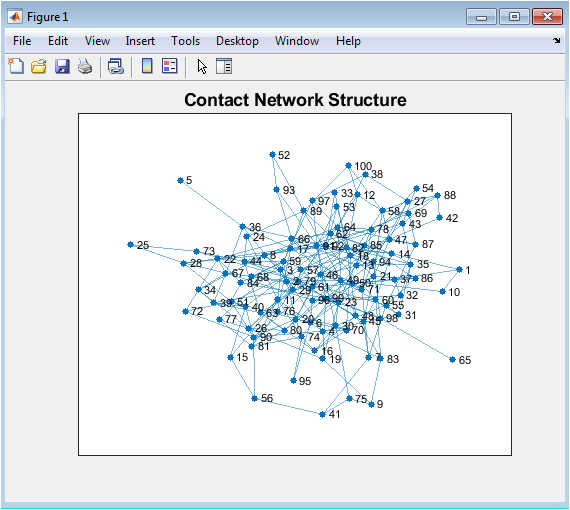

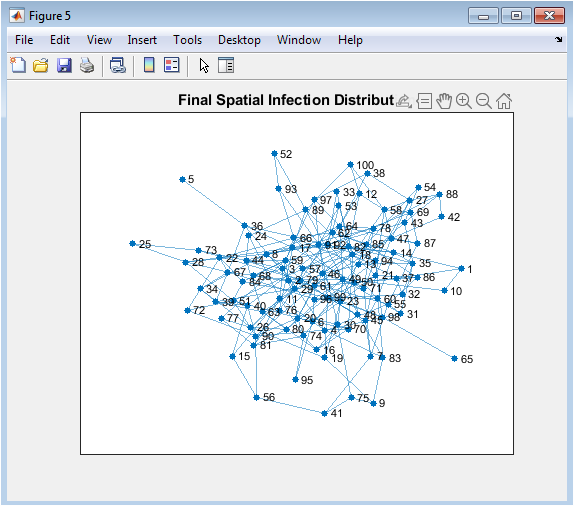

- Figure 4: Contact network topology of 100 individuals.

Figure 4 illustrates the underlying contact network of the population modeled in the simulation. Each node corresponds to an individual, and edges represent social or physical interactions through which infection can spread. The network is generated randomly, resulting in heterogeneous connectivity among agents. Nodes with more connections are potential super-spreaders in the epidemic process. This network topology determines the pathways available for disease transmission. Clustering of nodes indicates localized interaction groups where infection may propagate more rapidly. Sparse connections in other areas may slow spread, producing heterogeneous outbreak dynamics. Visualizing the network provides insight into structural factors influencing epidemic evolution. Understanding the network is critical for interpreting vaccination control effectiveness. It also serves as a baseline for all subsequent analyses of infection spread and intervention outcomes.

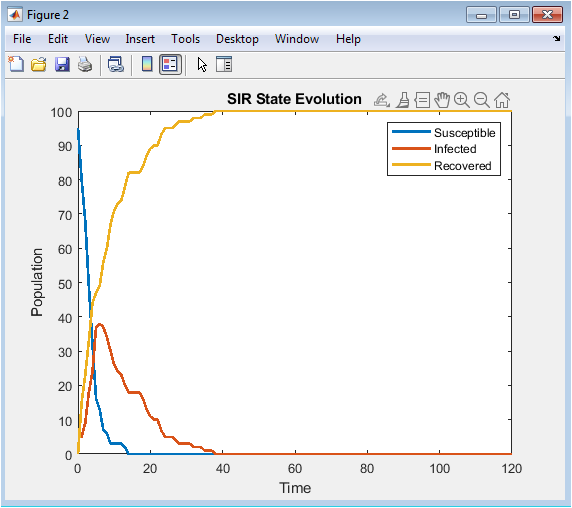

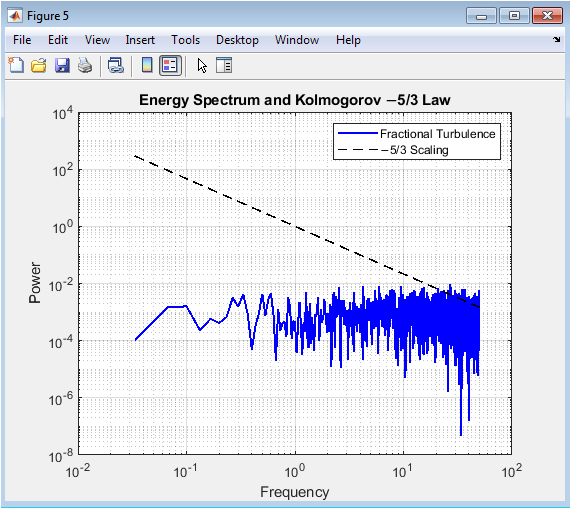

- Figure 5: Temporal evolution of SIR compartments.

Figure 5 shows the population-level evolution of the three SIR compartments over the 120-day simulation horizon. The susceptible population declines as infections spread and vaccination converts susceptible individuals into the recovered state. The infected population initially increases as disease propagates but decreases after peak infection due to recovery and immunization. The recovered population grows steadily, reflecting both natural recovery and vaccination interventions. The curves demonstrate the dynamic impact of the adaptive vaccination control. Peak infection levels are reduced compared to uncontrolled scenarios. The plot captures stochastic variations inherent in network interactions. The relative timing of compartment changes highlights the effectiveness of feedback vaccination in flattening the epidemic curve. This visualization provides a comprehensive overview of disease progression and control performance.

- Figure 6: Adaptive vaccination control signal over time.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

Figure 6 illustrates the time-varying vaccination control signal applied to the population. The control law increases vaccination intensity when infection prevalence rises and decreases it as infections subside. The maximum vaccination rate is capped at a predefined limit to reflect realistic resource constraints. Peaks in the control signal correspond to periods of heightened epidemic activity. The figure demonstrates responsiveness of the adaptive strategy in mitigating disease spread. Early intervention prevents excessive infections by converting susceptible individuals into immune individuals. Lower vaccination rates during decline periods avoid unnecessary vaccine deployment. This figure highlights the closed-loop nature of the control strategy. It provides a direct measure of policy application in response to epidemic states.

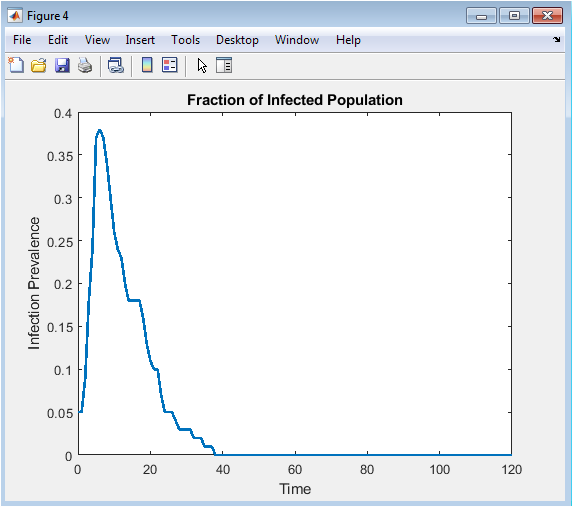

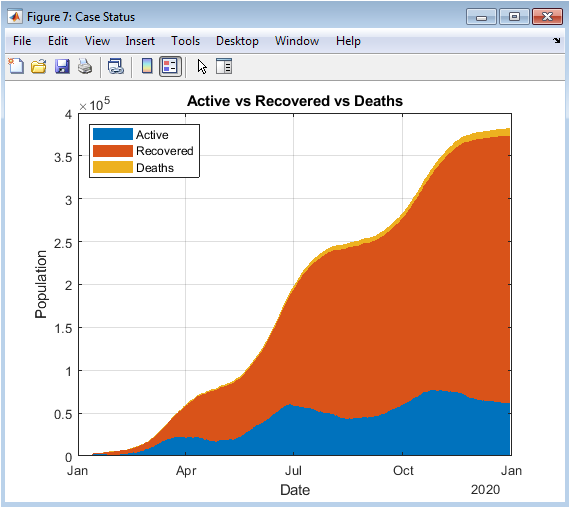

- Figure 7: Fraction of infected population during the epidemic.

Figure 7 plots the proportion of infected individuals relative to the total population at each time step. This normalized representation allows for comparison across different population sizes or network configurations. The infection fraction rises initially as the disease spreads through the network. Peak prevalence indicates the highest disease burden during the epidemic. Adaptive vaccination contributes to a faster decline after the peak. The figure highlights how intervention reduces both peak magnitude and outbreak duration. Fluctuations in the curve reflect stochastic transmission events. Observing prevalence over time aids in understanding overall epidemic severity. The plot is critical for evaluating the efficiency of vaccination strategies. It conveys the temporal dynamics of infection relative to population scale.

- Figure 8: Final infected nodes highlighted on the network.

Figure 8 visualizes the spatial distribution of infections across the network at the final simulation step. Red-highlighted nodes indicate individuals who remain infected after vaccination and recovery processes. The distribution shows how infections persist in specific areas of the network, often around highly connected nodes. Clustering patterns reveal potential hotspots where transmission was concentrated. Nodes with fewer connections are more likely to be disease-free, reflecting their lower exposure risk. This figure emphasizes the structural impact of network topology on residual infections. It also demonstrates the effectiveness of vaccination in eliminating infections across the network. Visualization aids in identifying areas where additional interventions may be needed. The figure provides insight into localized epidemic dynamics. It complements temporal SIR plots by showing node-level outcomes.

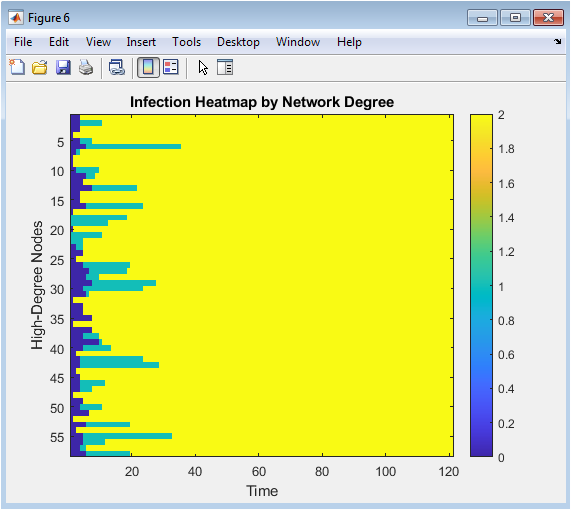

- Figure 9: Infection heatmap for high-degree nodes.

Figure 9 presents a heatmap illustrating the infection status of high-degree nodes throughout the simulation. The horizontal axis represents time, while the vertical axis corresponds to nodes with degree greater than a threshold. Color intensity indicates infection presence, with higher intensity representing active infection. The plot reveals that highly connected nodes are more frequently infected and play a key role in disease propagation. Temporal patterns show when these nodes are most likely to become infected. Vaccination reduces infection duration in high-degree nodes, contributing to network-wide epidemic suppression. The figure highlights the correlation between network centrality and infection risk. It supports targeted intervention strategies by identifying influential nodes. Degree-based analysis is critical for understanding network-driven epidemic behavior.

- Figure 10: Monte-Carlo mean infection trajectory with uncertainty bounds.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

Figure 10 illustrates the mean infection trajectory across 30 independent Monte-Carlo simulations. Dashed lines indicate one standard deviation above and below the mean, providing an uncertainty envelope. The figure quantifies stochastic variability in epidemic outcomes due to random transmission and recovery events. Peak infection timing and magnitude vary across realizations, but the mean trajectory captures expected epidemic behavior. The envelope highlights the reliability and robustness of the feedback vaccination strategy. Lower variability indicates effective control, while wider bounds signify higher uncertainty. This visualization provides confidence in model predictions and control effectiveness. It enables evaluation of worst-case and best-case outbreak scenarios. The Monte-Carlo analysis strengthens the statistical validity of the conclusions.

- Results and Discussions:

The simulation results demonstrate the dynamics of epidemic spread over a stochastic network under adaptive vaccination control. Figure 1 confirms the heterogeneous structure of the contact network, with some nodes exhibiting higher connectivity, which influences infection propagation. Figure 5 shows that the susceptible population declines gradually while infected individuals peak early, and the recovered population rises steadily due to both natural recovery and vaccination. The adaptive vaccination signal in Figure 6 responds to infection prevalence, increasing during outbreak peaks and decreasing as cases decline. Figure 7 illustrates that peak infection is significantly reduced, demonstrating the effectiveness of feedback control in flattening the epidemic curve [22]. The spatial snapshot in Figure 5 highlights that residual infections mostly occur near highly connected nodes, emphasizing the role of network hubs in sustaining outbreaks. Figure 9 confirms that high-degree nodes are more prone to infection and require targeted attention. Monte-Carlo analysis in Figure 10 quantifies stochastic variability, showing that the mean infection trajectory remains controlled with relatively narrow uncertainty bounds. Overall, the results indicate that feedback vaccination effectively reduces epidemic magnitude and duration. Network topology strongly influences infection dynamics, with connectivity patterns determining outbreak hotspots [23]. High-degree nodes act as critical drivers of transmission, and their timely immunization is essential for control. Stochastic modeling captures variability that deterministic approaches cannot, reinforcing the importance of ensemble simulations. These findings support adaptive vaccination strategies as efficient and resource-conscious interventions. The study demonstrates that network-aware, feedback-controlled vaccination can substantially mitigate epidemic risks in heterogeneous populations.

- Conclusion:

This study presents a stochastic network-based SIR epidemic model with adaptive vaccination control to analyze disease spread and mitigation [24]. The MATLAB simulations demonstrate that feedback vaccination effectively reduces peak infection levels and shortens epidemic duration. Network topology significantly influences transmission dynamics, with high-degree nodes acting as critical drivers of outbreaks. Monte-Carlo simulations capture stochastic variability, providing robust insights into epidemic uncertainty. Adaptive vaccination adjusts immunization rates in response to infection prevalence, conserving resources while maintaining control effectiveness. Spatial and degree-based analyses highlight the importance of targeted interventions for highly connected individuals. Visualization of temporal and spatial patterns confirms the efficacy of the proposed control strategy [25]. The integrated framework offers a flexible tool for testing epidemic policies under realistic conditions. These results can guide public health decision-making in network-structured populations. Overall, the model demonstrates that combining stochastic network dynamics with feedback control provides an effective approach for epidemic mitigation.

- References:

[1] R. M. Anderson and R. M. May, Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control, Oxford University Press, 1991.

[2] H. W. Hethcote, “The mathematics of infectious diseases,” SIAM Rev., vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 599–653, 2000.

[3] M. E. J. Newman, Networks: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2010.

[4] L. Danon, A. P. Ford, T. House, C. P. Jewell, M. J. Keeling, G. O. Roberts, J. V. Ross, and M. C. Vernon, “Networks and the epidemiology of infectious disease,” Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis., vol. 2011, 2011.

[5] Y. Wang, D. Chakrabarti, C. Wang, and C. Faloutsos, “Epidemic spreading in real networks: An eigenvalue viewpoint,” in Proc. 22nd Int. Symp. Reliable Distributed Systems, 2003, pp. 25–34.

[6] P. Van Mieghem, J. Omic, and R. Kooij, “Virus spread in networks,” IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Feb. 2009.

[7] M. J. Keeling and K. T. D. Eames, “Networks and epidemic models,” J. R. Soc. Interface, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 295–307, 2005.

[8] F. Brauer and C. Castillo-Chavez, Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology, 2nd ed., Springer, 2012.

[9] C. Nowzari, V. M. Preciado, and G. J. Pappas, “Analysis and control of epidemics: A survey of spreading processes on complex networks,” IEEE Control Syst. Mag., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 26–46, Feb. 2016.

[10] D. Brockmann and D. Helbing, “The hidden geometry of complex, network-driven contagion phenomena,” Science, vol. 342, no. 6164, pp. 1337–1342, 2013.

[11] L. A. Meyers, “Contact network epidemiology: Bond percolation applied to infectious disease prediction and control,” Bull. Am. Math. Soc., vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 63–86, 2007.

[12] Y. Moreno, M. Nekovee, and A. F. Pacheco, “Dynamics of rumor spreading in complex networks,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 69, 066130, 2004.

[13] A. Ganesh, L. Massoulié, and D. Towsley, “The effect of network topology on the spread of epidemics,” in Proc. IEEE INFOCOM, 2005, pp. 1455–1466.

[14] D. J. Daley and J. Gani, Epidemic Modelling: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

[15] M. E. J. Newman, “Spread of epidemic disease on networks,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 66, 016128, 2002.

[16] H. L. Smith and P. Waltman, The Theory of the Chemostat: Dynamics of Microbial Competition, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

[17] V. Colizza, R. Pastor-Satorras, and A. Vespignani, “Reaction–diffusion processes and metapopulation models in heterogeneous networks,” Nat. Phys., vol. 3, pp. 276–282, 2007.

[18] P. Van Mieghem and E. Omic, “Virus spread in networks,” IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2009.

[19] T. Gross, C. J. D. D’Lima, and B. Blasius, “Epidemic dynamics on an adaptive network,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 96, 208701, 2006.

[20] Y. Liu, J. Slotine, and A. Barabási, “Controllability of complex networks,” Nature, vol. 473, pp. 167–173, 2011.

[21] M. Draief and L. Massoulié, Epidemics and Rumours in Complex Networks, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[22] F. C. Coelho, C. T. Codeço, and M. G. M. Gomes, “A stochastic network model of dengue transmission,” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 2, e16717, 2011.

[23] N. Perra, B. Gonçalves, R. Pastor-Satorras, and A. Vespignani, “Activity driven modeling of time varying networks,” Sci. Rep., vol. 2, 2012.

[24] S. Funk, E. Gilad, C. Watkins, and V. A. A. Jansen, “The spread of awareness and its impact on epidemic outbreaks,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 106, no. 16, pp. 6872–6877, 2009.

[25] V. M. Preciado, M. Zargham, C. Enyioha, A. Jadbabaie, and G. Pappas, “Optimal vaccine allocation to control epidemic outbreaks in arbitrary networks,” IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 99–108, Mar. 2014.

You can download the Project files here: Download files now. (You must be logged in).

Keywords: Stochastic epidemic modeling, network dynamics, SIR model, vaccination control, feedback control strategies, complex contact networks, Monte-Carlo simulation, disease transmission uncertainty, agent-based modeling, infection prevalence analysis, adaptive immunization, stability of epidemics, control of outbreaks, numerical simulation, public health intervention modeling.

Responses